History of Perspective in Nativity Scene Art (Part One)

History of Perspective in Nativity Scene Art (Part One)

The posts are like a series:

if you miss the first chapter or skip the order, you’ll lose the thread 🧵

What does knowing history in general bring me?

Before talking about perspective, it is worth pausing on a broader question. You may ask yourself: “What does knowing history in general bring me?”. The answer is not only about art or nativity scene art, but about our very way of being human.

History gives us, above all, collective memory. Thanks to it, we know where we come from and we do not have to start from scratch with every generation. It reminds us of successes and failures, and allows us to learn from both.

At the same time, history gives us critical awareness. It prevents us from thinking that the present is natural or inevitable: we see it as the result of decisions, struggles, and contexts that could have been different. Knowing this background helps us look at our own time with greater clarity.

It also provides us with identity and belonging. We recognize in the traces of the past our customs, languages, and beliefs, and discover that we are part of something larger than ourselves. At the same time, it opens us to value other cultures and to place ourselves in dialogue with them.

History is also a horizon of the future. It is not only memory of the past, but a compass that guides us. Knowing how others faced changes and crises offers us paths and prevents naiveté. It invites us to move forward with greater meaning.

In short, history adds depth of vision. It allows us to perceive that today’s problems were already experienced in other ways, and that solutions do not arise out of nowhere, but from a thread of continuity. This awareness gives weight to our daily decisions.

Thus, knowing history in general brings us memory, identity, and judgment. And it is precisely from this foundation that it is worthwhile to approach the history of perspective: because it is not an erudite ornament, but a tool that illuminates what we do today when we create a nativity scene.

The quote “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” is widely attributed to the philosopher and writer George Santayana (1863 Madrid – 1952 Rome). [1]

The phrase appears in his 1905 work, The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress, specifically in volume 1, titled Reason in Common Sense. The full quote is: “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. When change is absolute there remains no being to improve and no direction is set for possible improvement; and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

What does knowing the history of perspective bring me?

You may be asking yourself: “All I want is to build a nativity scene for Christmas… so why should I care about the history of perspective?”. The question is legitimate, and it deserves an answer before we go deeper into this journey.

Perspective did not begin as a simple optical trick: it is the trace of how each age understood the world. From medieval frescoes to the Renaissance, and later to the modern avant-garde, every shift in perspective reflects a cultural and aesthetic transformation. Knowing this path places the nativity scene artist within a larger artistic tradition. It is not about repeating formulas, but about understanding that, in composing a nativity scene, one takes part in a history that has shaped our way of seeing.

History, in general, is not a catalog of forgettable dates, but a memory that sheds light on the present. Seeing is never a neutral act: every representation implies an interpretation of the world. That is why each nativity scene you create—even in your living room—proposes a visual order, a way of arranging the figures and narrating the mystery. Perspective is, in this sense, a language that speaks of our relationship with reality and with the divine.

In the practice of nativity art, what we seek is emotion and coherence. If you are unaware of how perspective was born and evolved, you risk applying it superficially. By knowing its history, you understand why certain resources work, why others feel forced, and how to give your scene depth and life. Perspective not only organizes space: it also helps to persuade both the eye and the heart.

You may not have thought that the history of perspective had so much to do with your nativity scene. Yet without it, scenes remain flat or silent. With it, they become visual narratives full of depth and meaning.

A practical example: classical music

Let us think about classical music. What sense would it make to perform Beethoven without knowing that he lived in a time of transition between Classicism and Romanticism? Or to listen to Bach without understanding that his work crowns an entire Baroque tradition of counterpoint and polyphony? Each composition is not an isolated sound, but the voice of an era, a chapter within a greater evolution.

That is why someone studying classical music does not limit themselves to learning notes and scales: they need to know the history of that art. Only then can they understand why some works sound solemn while others seek intense emotion; why some follow strict rules and others break them with boldness.

It is the same with the nativity scene. You could simply place figures and houses, just as you could play notes on a piano with no further thought. But when you understand the history of perspective—just as the musician understands the history of music—you discover a language with roots, evolution, and meaning. And then your nativity scene ceases to be only a decoration and becomes a creation with cultural and artistic depth.

Ancient history of perspective

A look back: the first steps of perspective

The history of perspective does not begin in the Renaissance, even though it reached its mathematical formulation there. Long before, ancient cultures had already sensed that the human eye perceives space in complex ways and that representing it was no simple task.

From prehistory to Egypt: the first attempts

The desire to represent space and give visible form to what is perceived did not arise with historical civilizations. Already in prehistory we find attempts to suggest depth. In the cave paintings of Lascaux or Altamira, animals are shown with overlapping figures and variations in size: the larger ones appear in the foreground and the smaller ones behind. In some cases, legs and horns are painted at an angle, as a timid foreshortening. This was not yet a system of perspective, but an intuitive resource to evoke three-dimensionality.

In Paleolithic sculpture, such as the famous Venus figurines, the focus was symbolic: certain features, such as reproductive organs, were exaggerated, while others, such as the face, were omitted. The goal was not optical mimesis but the expression of vital and religious values. These works remind us that, long before any theory of perspective, human beings were already seeking to represent the invisible and to give meaning to the world through images.

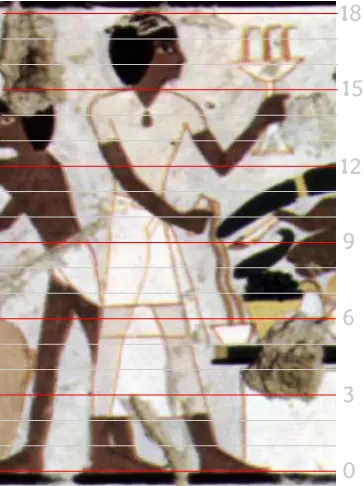

Egypt: symbolic clarity over realism

Egyptian art did not seek to reproduce visual reality, but rather to express a religious and symbolic order. For this it was governed by a canon of proportions, based on a grid of 18 squares in height that was used from the Middle Kingdom onward. Each key point of the body—elbows, knees, navel, shoulders—corresponded to a line of this grid. In this way, all figures maintained “ideal” and standardized proportions, considered correct from a cultural and spiritual perspective. This system explains the uniformity of Egyptian art over millennia. However, it was not a prison: findings show slight variations, indicating that the grid functioned more as a guide than as an inflexible rule.

Equally important was the law of frontality, which combined profile and frontal views to show the clearest aspect of each part of the body: the head and legs in profile, the eyes and torso frontally. The goal was not to imitate what the eye sees, but to provide a complete and eternal image of the person or the deity represented. For the same reason, foreshortening was avoided: a foot in profile was considered more “truthful” than a foot in perspective, which would have distorted the perfect form.

The representation of time and movement followed this same logic. A single figure could combine in one gesture different phases of an action, so that a farmer plowing might be shown with arms in positions suggesting both the beginning and the end of the task.

Color was also symbolic: red represented life and strength; white, purity; black, the fertility of the Nile and death; yellow, the sun and eternity. Men’s skin was usually painted in reddish tones, while women’s skin appeared lighter—conventions that reflected social codes more than naturalistic observation.

Hierarchy was expressed through size and position: the most important figures were shown larger or placed at the top of the composition, a system sometimes called vertical perspective. To reinforce this logic, overlapping was used, placing some figures in front of others to suggest proximity. All of this demonstrates that Egyptian art was not a technical limitation, but a conscious and elaborate system, consistent with a religious worldview that prioritized clarity and eternity over visual realism.

Greece: the illusion of space on stage

In the Greek world, perspective did not emerge as a unified, scientific system —as it would centuries later in the Renaissance— but as an experimental practice tied to observation and workshop experience. These attempts did not aim to reproduce vision mathematically, but to create a convincing effect before the viewer’s eyes.

The Greek term closest to our idea of perspective was skenographía [5], literally “painting of the scene.” Born in the context of theater, it referred to stage sets that simulated architecture and created the illusion of depth. Aristotle considered it the sixth constitutive element of theatrical representation, not a mere accessory. For Aristotle, the power of tragedy lay in the plot (the fable) and the characters, not in visual effects. The spectacle was a necessary but secondary component. Vitruvius mentions the painter Agatharchus of Samos [6] as the author of a stage set around the mid-5th century BC. He also attributes to him the writing of a treatise on this practice, regarded by some as the first known text on perspective. Although it was tied to scenography, its importance lies in the fact that it set rules and opened the way to later reflections by philosophers such as Democritus and Anaxagoras.

Skenographía was closely linked to skiagraphía [7], the art of painting shadows. This technique, already mentioned by Aristotle, was one of the earliest attempts to give figures volume through tonal gradation. In this sense, it can be considered the earliest origin of the sense of perspective, since it made it possible to move from flat two-dimensionality to a representation with a certain visual depth.

The reflection on space expanded into the scientific realm. Around 300 BC, Euclid wrote his treatise Optics [9], in which he analyzed how the perceived size of an object depends on its distance from the eye. Although he did not formulate a system of central perspective, his observations laid the groundwork for linking vision and geometry, a decisive step in the history of perspective.

Greek pottery and, later, Italiote pottery from the 5th and 4th centuries BC [10] [11] reflect this search for depth. Architectures in foreshortening, temples, altars, and columns appear receding with strong perspective lines, often combined with figures represented frontally or in tiers. In a single scene, perspectival and non-perspectival devices could coexist, revealing an interest in illusion rather than geometric consistency.

Artist painting a statue of Heracles.

With Hellenism, these experiments reached a greater degree of plausibility. Spaces became more coherent and convincing, although they never formed a central and unified system. These advances paved the way for the spectacular frescoes of the Second Pompeian Style, where architectural illusionism achieved its highest development in Antiquity.

In short, the Greek contribution was decisive: perspective was understood as a tool to move and persuade, rather than as a mathematical construction. What mattered was not accuracy, but visual effectiveness before the viewer. A principle that, centuries later, would remain alive in the nativity scene: what matters is not that space be perfect, but that it appear true and stir the heart of the beholder.

Rome: between practice and spectacle

If Greece had laid the theoretical and scenographic foundations of perspective, in Rome the concern for illusionism was carried above all into decorative and architectural practice. We do not find a single coherent system, but rather a set of increasingly sophisticated techniques aimed at astonishing the viewer.

The Romans inherited skenographía from the Greeks and took it further in wall painting. In the frescoes of Pompeii and Herculaneum—especially in the so-called Second Pompeian Style [14], developed in the 1st century BC—there appear fictive architectures that open the walls toward landscapes, porticoes, and receding columns. These decorations not only visually expanded domestic spaces but also expressed the power and cultural refinement of their owners.

A remarkable example is the frescoes of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor [15] in Boscoreale, where multiple vanishing points are used to construct an illusionistic space. Although not always consistent from a geometric standpoint, they clearly show a desire to experiment with depth and to create settings that seem to extend beyond the real wall.

In addition to architectural perspective, the Romans explored what we now call atmospheric (aerial) perspective [16]. In the famous Underground Garden of the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta (c. 30 BC) [17], vegetation is depicted with great naturalism: the nearest plants appear sharp and detailed, while those farther away fade into bluish tones with less contrast, creating the sensation of distance. This device, also found in frescoes such as Paris on Mount Ida, shows that the Romans sensed how the atmosphere alters our perception of space. In this way, they anticipated a principle that centuries later would be revived in the Renaissance under the name of aerial perspective.

Roman artists also applied perspective in the decoration of vaults and ceilings, painting beams and coffers that converged toward a point to suggest height and monumentality. These devices, although empirical and not systematic, demonstrate a keen observation of how we perceive space and a remarkable ability to manipulate the viewer’s vision.

However, Rome did not develop a mathematical theory of perspective. Its interest was primarily practical: achieving a convincing effect in villas, temples, or theaters. For this reason, many frescoes combine areas of great illusionism with others that follow flatter, more traditional conventions. The priority was not absolute coherence, but visual and narrative impact.

Overall, the Roman contribution was decisive for the history of perspective: it transformed Greek experiments into an art of appearance in the service of spectacle and everyday life. This legacy was transmitted for centuries through frescoes and mosaics until the Renaissance reinterpreted it with a mathematical and systematic language.

Middle Ages: multiple languages for a single space

After the splendor of Rome, the representation of space entered a new cultural framework. To understand its evolution, we will follow a chronological order: first Byzantine art, the direct heir of the Roman tradition; then Islamic and Chinese art, which developed their own solutions; and finally Western European art, where experiments emerged that anticipated the Renaissance. All these traditions shared a common feature: they did not seek central linear perspective, but adapted spatial representation to their own cultural, religious, or aesthetic values.

Byzantine art

In Byzantium, the so-called reverse perspective [21] was developed, where the lines do not converge inward but open outward toward the viewer. In this way, the scene seems to expand outward, directly involving the believer in the sacred space. The goal was not to create a realistic illusion, but to emphasize that the divine transcends the laws of human vision. This convention became a characteristic feature of Byzantine icons and marked a clear difference from the optical explorations of the classical world.

The Islamic world

In the Islamic sphere, the representation of space followed a different logic. Linear perspective was avoided, and geometry, symmetry, and decoration were prioritized. In Persian miniatures and manuscripts of the Abbasid period (8th–13th centuries), a form of oblique perspective was used: the more distant objects were placed at the top of the composition, creating a stepped sense of depth. However, most of these works were destroyed during the Mongol invasions, and what we know comes mainly from chronicles and indirect references. For this reason, we do not have representative images from that early period, although its legacy was passed on to later miniatures in Iran and Central Asia.

Chinese art

In China, very early on, oblique projection was developed, a system different from both Byzantine and Islamic traditions. Instead of a single vanishing point, space unfolded in successive layers: mountains, rivers, and trees were arranged in oblique planes that suggested depth without the need for a horizon or proportional reduction. This convention, used for centuries, gave Chinese landscape painting its own expressiveness, more connected to spiritual contemplation than to visual realism.

Western Europe

In Romanesque art, the frescoes of churches such as San Clemente de Tahull (12th century) follow a symbolic logic: flat, hierarchical figures, with schematic buildings lacking spatial coherence.

In this famous fresco, perspective is not used to create depth. On the contrary, the figure of Christ dominates the composition through his monumental size, which emphasizes his divinity and power. The figures of the apostles and the symbols of the evangelists are much smaller, despite being on the same plane. The representation of architecture is highly simplified and symbolic, not an attempt to create a habitable space. [24]

The revolution of Giotto

Until then, painting had been above all a symbolic art: flat figures, abstract backgrounds, and an absence of depth. With the Gothic period, more naturalistic solutions began to be tried, but the true transformation came with Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337) [25] in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (c. 1305) [26]. His work marked a decisive turning point in the history of art: it gave painting a new purpose, that of imitating life and human emotion.

Giotto broke with this system and gave his figures realism and humanity. His innovation lay in three fundamental aspects:

- Volume and weight of the figures. Giotto was the first to give his characters a weight and solidity that anchor them in space. He achieved this through chiaroscuro, modeling forms with light and shadow so that they looked like sculptures painted on the wall. In a way, he revived and carried much further a device already intuited in Greek skiagraphía, the art of painting shadows. But while in Antiquity it was a limited experiment, in Giotto it became a structural principle that gave his figures physical and dramatic presence.

- The pictorial stage. Giotto revolutionized the conception of space: his scenes unfold in architectural settings and landscapes that function as a unified and believable stage, where the characters act as in a play. Examples such as The Lamentation over the Dead Christ [27] show how the composition guides the viewer’s gaze, achieving a coherent and persuasive visual narrative.

- The birth of psychodrama. Giotto’s characters are no longer rigid symbols, but human beings with recognizable emotions. Their faces and gestures express pain, wonder, compassion, or despair, bringing religious scenes closer to the viewer with unprecedented force. Giotto did not just paint stories—he painted feelings.

Giotto did not formulate a mathematical system of perspective, but he created the need for one. By constructing pictorial worlds that felt real and three-dimensional, he prepared the ground for Masaccio and Brunelleschi to develop linear perspective in the Renaissance. For this reason, he is considered the father of the Renaissance: he was the first to break with the past and to lay the foundations of spatial and human representation that would dominate Western art for the centuries to come.

1304-06, fresco, 200 × 185 cm. Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel), Padua.

In Christ before Caiaphas (Scrovegni Chapel), Giotto experiments with a “eyeballed” linear perspective. The layout shows two different behaviors: the ceiling beams (blue lines) consistently converge toward a vanishing point Oblue, while the edges where the wall meets the ceiling (green lines) converge toward a different vanishing point, Ogreen. This double convergence reveals that Giotto did not apply a single geometric system, but rather an empirical construction to achieve plausibility and guide the gaze.

In a “pure” central perspective, all the orthogonals of the room (beams, floor, cornices) that are parallel in real space should share the same vanishing point O. Here, the separation between Oblue and Ogreen creates a slight torsion of space: the ceiling pushes toward a perceptual center, while the walls open the box toward the sides. Moreover, the resulting vanishing point does not coincide with the geometric center of the image—which is not obligatory—but during the Renaissance it will tend to stabilize on the horizon line and unify the spatial “box.”

Read historically, the fresco shows a proto-perspective: enough to anchor the figures in a believable place and focus the narrative attention on Christ, but without the mathematical homogeneity that Brunelleschi and Masaccio would establish a century later.

For the nativity scene artist (practical application): if you design an interior with central perspective, align beams, cornices, and floor toward a single vanishing point; if you choose to use two, treat them as two boxes with different axes and disguise the transition with arches, columns, or drapery to avoid the impression of a “broken space.”

Terminological note: here we use “vanishing point” (not “viewpoint”). The vanishing point is in the picture; the viewpoint is the observer’s position and determines the horizon line and the location of the vanishing points.

We also mention in passing the orthogonal or convergent lines, but we do not yet develop their technical definition. These concepts will be addressed in detail in later chapters of the manual, specifically dedicated to constructing perspective in the nativity scene.

The connection between Giotto and nativity scene art

Giotto’s great revolution was not only technical but also one of mindset. He humanized the divine, bringing sacred figures closer to the viewer through emotion and real space. This is precisely where the connection with figurative nativity scene art lies.

A truly artistic and emotionally powerful nativity scene is not a simple collection of symbolic figures. It is a scene that aspires to be a fragment of life. To achieve this, it needs:

- Figures that feel. Mary and Joseph are not icons; they are a mother and father looking tenderly at their child. The shepherds are not just witnesses; they are people expressing wonder and devotion.

- A believable space. The figures are placed in a setting with depth: a cave, a stable, or a landscape that the viewer recognizes as real.

- Narration of the story. The composition guides our gaze so that the story of the Nativity comes to life and awakens emotion.

All these elements —humanity, emotion, and spatial believability— are the very same innovations that Giotto introduced into painting. He laid the groundwork for the Nativity to move beyond being a mere symbol and become an aesthetic and emotional experience that still lives on today in the nativity scene.

The union of St. Francis’s vision and Giotto’s genius

Consider this: St. Francis and Giotto pursued a similar goal through different means: bringing the sacred closer to human experience, making it tangible and emotionally accessible.

- The act of St. Francis (1223, Greccio). The first living nativity was not simply a representation, but a sensory and emotional experience so that the faithful could feel the humility and poverty of Christ’s birth. It was a direct response to a tradition that, until then, had represented the Nativity in a solemn and distant way. St. Francis humanized the mystery.

- Giotto’s response (1295, Upper Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi). Probably familiar with Greccio —and traditionally attributed to him is a fresco of that scene in the Basilica of Assisi— [28], Giotto gave that vision the visual language it needed. His innovations in the Scrovegni Chapel were the perfect vehicle for that Franciscan intention.

Part of Scenes from the Life of St. Francis.

Two keys to that encounter

- Humanization of the mystery. Giotto painted Mary, Joseph, and the shepherds as real people who feel: presence, tenderness, wonder, devotion. This is the same humanity sought by St. Francis.

- Realism of the setting. The Nativity appears in an environment with depth —cave, stable, landscape—; believable light and atmosphere that the viewer can “inhabit.” Precisely the verisimilitude pursued by the living nativity.

Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel), Padua.

Conclusion. If St. Francis is credited with conceiving the nativity scene as a living experience, Giotto can be seen as the other side of the coin: its visual and emotional representation. One did it through faith; the other —the form Giotto invented— through art. Together they opened a path that transformed the way Christianity was understood and represented in the West, of which figurative nativity scene art is a direct heir.

After Giotto, other artists continued this search. The Master of Vyšší Brod [30], in his Cycle of the Life of Jesus: Nativity (1350), depicted a space that was still hierarchical but more integrated.

Around 1390, Lorenzo Monaco [31] took a step further in his Nativity of Jesus, with architectures suggesting depth and a greater sensitivity to light.

Finally, Ambrogio Lorenzetti [32], in The Presentation in the Temple (1342), experimented with converging lines on the floor, directly anticipating linear perspective. All these examples show how, in Western Europe, the ground was being prepared for the great perspectival revolution of the Renaissance.

This work is a clear precursor of the Renaissance. Lorenzetti attempts to create a coherent space: the lines of the marble floor and the bases of the columns converge toward a central vanishing point. Although the lines are not perfectly aligned, the artist demonstrates an advanced understanding of how human vision perceives space. It is a conscious experiment to unify the scene within a single architectural setting.

Fresco painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Hall of the Nine of Siena’s Town Hall [34]

Thus, the Middle Ages were not a time of emptiness but of diversity. Each tradition sought its own way of organizing space, whether symbolic, decorative, or contemplative. All kept the problem of representation alive, even if without resolving it into a single system. This search prepared the ground for the Renaissance, when for the first time a central linear perspective, coherent and universal, was formulated.

References:

- ↑ [1] George Santayana – Wikipedia (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Santayana

- ↑ [2] File:Lascaux II.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lascaux_II.jpg

- ↑ [3] Venus de Lespugue – Viquipèdia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_de_Lespugue

- ↑ [4] File:Ägyptischer Maler um 1500 v. Chr. 001.jpg - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ägyptischer_Maler_um_1500_v._Chr._001.jpg

- ↑ [5] Notas de arte Clásico y Helenístico: Skenographía. Espacio ilusionista y percepción visual en ei mundo clásico. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.notasdearteclásicoyhelenístico.com/2019/07/skenographia-espacio-ilusionista-y.html

- ↑ [6] Agatarco – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agatarco

- ↑ [7] Skiagraphia – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skiagraphia

- ↑ [8] Cerámica apulia – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerámica_apulia

- ↑ [9] Óptica de Euclides – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Óptica_de_Euclides

- ↑ [10] Denoyelle, M., & Iozzo, M. (2011). Martine Denoyelle et Mario Iozzo, La céramique grecque d’Italie méridionale et de Sicile. Productions coloniales et apparentées du VIIIe au IIIe siècle av. J.-C., 2009. L’Antiquité Classique, 80(1), 593–595. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://search.worldcat.org/es/title/912435914

- ↑ [11] InStoria - Ceramica italiota a figure rosse. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.instoria.it/home/cratere_apulo_ceramica_iconografia.htm

- ↑ [12] Crátera – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crátera

- ↑ [13] File:Pompei maison mysteres fresque.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompei_maison_mysteres_fresque.jpg

- ↑ [14] Estilos pompeyanos – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estilos_pompeyanos

- ↑ [15] Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale - Roman - Late Republic - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017

- ↑ [16] Perspectiva aérea – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perspectiva_aérea

- ↑ [17] Villa of Livia – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_of_Livia

- ↑ [18] File:Livia Prima Porta 10.JPG - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Livia_Prima_Porta_10.JPG

- ↑ [19] File:Pompei 2015 (18681704868).jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved September 13, 2025, from (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompei_2015_(18681704868).jpg

- ↑ [20] Villa de los Misterios – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_de_los_Misterios

- ↑ [21] Perspectiva invertida – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perspectiva_invertida

- ↑ [22] File:Italo-Byzantinischer Maler des 13. Jahrhunderts 001.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Italo-Byzantinischer_Maler_des_13._Jahrhunderts_001.jpg

- ↑ [23] File:Water Mill (闸口盘车图) by Wei Xian 卫贤 (Five Dynaties).png - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Water_Mill_(闸口盘车图)_by_Wei_Xian_卫贤_(Five_Dynaties).png

- ↑ [24] File:(Barcelona) Frescos of Sant Climent de Taüll.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:(Barcelona)_Frescos_of_Sant_Climent_de_Taüll.jpg

- ↑ [25] Giotto di Bondone– Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giotto_di_Bondone

- ↑ [26] Capilla de los Scrovegni – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capilla_de_los_Scrovegni

- ↑ [27] File:Compianto sul Cristo morto.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Compianto_sul_Cristo_morto.jpg

- ↑ [28] Saint Francis cycle in the Upper Church of San Francesco at Assisi - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Saint_Francis_cycle_in_the_Upper_Church_of_San_Francesco_at_Assisi

- ↑ [29] File:Birth of Jesus - Capella dei Scrovegni - Padua 2016.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Birth_of_Jesus_-_Capella_dei_Scrovegni_-_Padua_2016.jpg

- ↑ [30] Master of Vyšší Brod – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Master_of_Vyšší_Brod

- ↑ [31] Lorenzo Monaco – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenzo_Monaco

- ↑ [32] Ambrogio Lorenzetti – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambrogio_Lorenzetti

- ↑ [33] File:Ambrogio Lorenzetti - Presentazione di Gesù al tempio - Google Art Project.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ambrogio_Lorenzetti_-_Presentazione_di_Gesù_al_tempio_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

- ↑ [34] File:Ambrogio Lorenzetti Allegory of Good Govt.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ambrogio_Lorenzetti_Allegory_of_Good_Govt.jpg