Two Paths to Reality: The Challenge of Perspective

Two Paths to Reality: The Challenge of Perspective

The posts are like a series:

if you miss the first chapter or skip the order, you’ll lose the thread 🧵

At the beginning of the 15th century, European artists faced the same problem: how to create the illusion of three dimensions on a flat surface? The answer was not a single one. Two distinct methodologies emerged, born in different cultural contexts but sharing the same goal: to turn painting into an illusionistic and believable window onto reality. A challenge that, centuries later, we still face as nativity scene artists striving to create coherent miniature worlds.

In Italy, particularly in Florence, perspective was conceived as a form of science and reason. Through the work of Brunelleschi, Masolino da Panicale, Masaccio, and Alberti, geometry and mathematics became the foundation of a linear system that organized space around a vanishing point.

In Flanders —the Low Countries and present-day Belgium— the path was different. Painters such as Jan van Eyck or Rogier van der Weyden did not start from geometry, but from empirical observation. Their perspective was optical and atmospheric: based on light, reflections, and minute detail. This approach, closer to the human eye than to mathematical rules, offered a sensitive and almost tactile vision of the depicted world. In nativity scene art, we work precisely with this double vision —geometric rigor and sensitive appearance— to build a coherent and emotionally convincing illusion.

Reminder (Manual): in nativity scene art we use both approaches —the Italian geometric rigor and the Flemish sensitive appearance; we do not limit ourselves to strict architectural perspective.

That is why, if you are intrigued by what is rarely explained, keep reading: you will surely find ideas useful for building your own nativity scenes.

How to Read this Parallel

To clearly understand the evolution of perspective in the 15th century, we will not follow a single European chronological thread. The story split into two parallel paths, and only by studying them side by side can we appreciate the magnitude of the transformation it brought to art and visual perception.

Italy (Florence): we will explore how architects, painters, and sculptors, beginning with Brunelleschi’s experiments, developed a geometric method that laid the foundation for linear perspective.

Flanders (Low Countries and Belgium): we will see how Flemish painters, from Jan van Eyck to the miniaturists of the Très Riches Heures, shaped an optical and atmospheric perspective, based on close observation of light, ambiance, and materials.

These two processes should not be understood as successive stages —first Italy and then Flanders— but as simultaneous and complementary responses to the same visual challenge. While Florence sought to construct a rational, mathematically ordered space, the North pursued visual fidelity that captured the subtleties of light, reflections, and textures of the sensible world.

The Scenographic Synthesis: Reason and Sensibility for the Nativity Artist

Ultimately, what nativity scene artists seek is to create a scene that conveys depth and visual truth, capable of moving through scenography. That is why it is so valuable to know both traditions: the geometric precision of Italy and the optical sensitivity of Flanders. Fused together, they offer nativity art a complete visual language, where the rule —or the string that marks vanishing lines— and the eye unite to bring the sacred space of the nativity to life.

Let us begin, then, with Italy. It was there, in the heart of Renaissance Florence, that perspective ceased to be a workshop secret and became a science, the cornerstone of any scenography that aspires to combine emotion, order, and depth.

Perspective as Science in Florence

In 15th-century Florence, the Renaissance [1] opened a new horizon. There, linear perspective ceased to be an isolated resource, based on practice and intuition, and began to be understood as a scientific language grounded in optics, geometry, and mathematics. This process was gradual: pioneers emerged, resistances appeared, and for a time the new vision coexisted with forms of representation inherited from the medieval world. It was not only a technical discovery but a change of vision, capable of ordering space according to precise, rational, and verifiable rules.

Painting, sculpture, and architecture then ceased to be considered mere manual crafts and came to be seen as applied sciences, founded on measurable and demonstrable principles. This transformation also dignified the artist: no longer just an “artisan” executor, but a thinker, an intellectual able to conceive and demonstrate visual ideas.

The consolidation of this system in Florence was the work of key figures. Filippo Brunelleschi carried out the experiments that empirically revealed the principle of the vanishing point. Masolino, in the Goldman Annunciation (1424), and Donatello, in the relief The Feast of Herod (c. 1425), were pioneers in applying these rules to painting and sculpture. Shortly after, Masaccio used perspective with unprecedented narrative force in the Trinity (c. 1427) and in the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel.

The method was systematized by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise De pictura (1435), which elevated painting to the rank of an intellectual discipline. Piero della Francesca advanced toward a purer mathematical vision in De prospectiva pingendi, while his pupil Luca Pacioli reinforced the geometric foundation in the Divina proportione, illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo also expanded the horizon with his research on aerial perspective, introducing gradations of light and atmosphere.

Finally, Raphael achieved an exemplary synthesis in the School of Athens (1510), where classical monumentality, linear precision, and the first solutions of oblique perspective are integrated. With him, scientific perspective reached its maturity within the Renaissance ideal.

The Chronological Approach

In this section we will focus on the first works created before 1435, the year in which Leon Battista Alberti published his treatise De pictura and turned a workshop secret into written theory. Until then, linear perspective was transmitted orally and practically, circulating among architects, sculptors, and painters in the Florentine environment.

The order we will follow will not be biographical, but based on the earliest works where one-point linear perspective clearly appears. This approach will allow us to observe, step by step, how the new science of space was consolidated. We will begin with Masolino’s early attempts in the Foundation of Santa Maria Maggiore, continue with Donatello’s low-relief sculpture, and move through the narrative scenes of the Brancacci Chapel. From there, we will see how Masaccio reached monumental rigor in the Trinity, a turning point that opened the way for the devotional elegance of Fra Angelico, the geometric obsession of Paolo Uccello, and the mathematical culmination of Piero della Francesca.

Methodological Note: Many attributions in the Quattrocento present margins of doubt. Some dates are documented through contracts or inscriptions, while others are established through stylistic and comparative analysis. Here we follow the chronology most widely accepted by specialized historiography, with the aim of helping the reader understand the progressive development of perspective in its early decades.

Filippo Brunelleschi and the Discovery of Perspective

In early 15th-century Florence, the architect, engineer, and sculptor Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)[2] carried out the experiments that would establish him as the true discoverer of linear perspective[3]. Up to that point, painters such as Giotto, Duccio, or Ambrogio Lorenzetti had attempted spatial approaches, but without a scientific basis or systematic use of the vanishing point.

Scientific Roots: from Alhazen to Brunelleschi

Brunelleschi’s breakthrough was not an isolated act, nor did it emerge from nothing. Centuries earlier, the Arab scientist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen; c. 965–c. 1040)[5] had formulated in his Book of Optics (1011–1021)[6] —later translated into Latin as De aspectibus— the theory that vision occurs because light enters the eye in straight lines. This principle legitimized the geometric representation of the visible world.

These ideas reached Europe through medieval thinkers such as Roger Bacon (c. 1220–1292)[7] and Witelo (c. 1230–1280/1314?)[8], author of the influential Perspectiva. Witelo not only systematized Alhazen’s optics but also introduced reflections on the psychology of vision —association of ideas, perception, and memory— and on light as a divine emanation, in harmony with medieval Platonism.

This optical legacy —from Alhazen to Bacon and Witelo— was part of the intellectual context of the Renaissance. Although Brunelleschi conducted his experiments around 1415 without leaving written records, those notions about vision were already circulating among learned circles. Decades later, Lorenzo Ghiberti[9], in his Commentario terzo (1452–1455)[10], confirmed the direct influence of these sources (Alhazen, Ptolemy, Bacon) in providing theoretical foundations for the visual arts. Ghiberti’s treatise demonstrates that the scientific background of perspective was present and active in the environment where Brunelleschi developed his method.

Historical Note: Alhazen’s work did not remain confined to Latin scholastic circles. By the late 14th century it had been translated into Italian as De li aspecti, making these ideas accessible to goldsmiths, sculptors, and painters without academic training in Latin. This helps explain how they could influence figures like Ghiberti or Brunelleschi himself.

A. Mark Smith, Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 91(5), 2001. He notes that, through Ghiberti, Alhazen’s Book of Optics “may well have been central” to the development of artificial perspective in early Renaissance Italian painting.

David C. Lindberg, Roger Bacon and the Origins of Perspectiva in the Middle Ages, Clarendon Press, 1996.

Current resource: the Thinking 3D: Book on Optics[11] project offers a visual introduction to Alhazen’s Book of Optics and its influence on Western perspective.

The Panel Experiments

Brunelleschi painted two small panels: one with a view of the Baptistery of San Giovanni[12] and another with the Piazza della Signoria[13]. In the first, he drilled a hole at the eye-level viewpoint and, by placing a mirror in front, managed to make the painting coincide exactly with the real view of the building. Thus, he demonstrated that all parallel lines converge at a single distant point: the vanishing point. In the second panel, he cut out the profile of the buildings to compare them directly with the actual piazza. Although the panels have not survived, we know of these experiments thanks to the testimony of his biographer, Antonio Manetti[14].

Didactic Note:

Architecture as a Laboratory

Brunelleschi applied these same proportional rules in his architectural work. For him, a building had to be conceived from the viewer’s standpoint, respecting the logic of a single viewpoint. His dome of Santa Maria del Fiore[15][16] is not only a technical marvel but also a visual manifesto of harmony and proportion. In his case, architecture became a true laboratory of perspective, where the laws of drawing were translated into real construction.

Brunelleschi’s Legacy in Renaissance Perspective

Through his visual experiments, Filippo Brunelleschi opened a path that forever changed the way space was represented. From that turning point onward, various artists and theorists on the Italian peninsula began to apply —and to transform— the new rules of linear perspective. Before Alberti codified them in writing, perspective was already being tested in concrete works, circulating as practical knowledge among architects, sculptors, and painters.

Before 1435: the first experiments in perspective

Early fifteenth-century Quattrocento Florence was a true laboratory of ideas. Architects, sculptors, and painters shared spaces, workshops, and commissions, and Brunelleschi’s discovery spread by word of mouth, without the need for treatises. Masaccio, a close friend of Brunelleschi, was part of that environment described by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)[17], which also included Masolino, Donatello, and other artists connected to the church of the Carmine and the San Niccolò Oltrarno neighborhood.

Perspective had not yet been codified, but it was already a subject of conversation, experimentation, and informal transmission among colleagues. It was not learned from books, but in the workshop, with hands and eyes. It was shared knowledge in the making, born within a community of artists who, without fully realizing it, were inventing a new way of seeing.

Historical note: Artistic life in Florence was not limited to the great palaces in the city center but had its working heart in neighborhoods like San Niccolò, where artists lived, worked, and shaped the new artistic language. Modern studies on guild organization and the daily life of artists —such as those by Richard A. Goldthwaite, The Building of Renaissance Florence[18], and Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy[19]— analyze in detail how the workshop system functioned and highlight the importance of personal interaction and competition. The location of many of these workshops in the Oltrarno remains a recurring theme in contemporary historiography.

Masolino da Panicale: the transition toward a new vision

Masolino da Panicale (1383–1447)[20] represents a key transitional moment in Quattrocento painting. Older than Masaccio (1401–1428), and trained in the elegant style of the Italian International Gothic[21], he was nonetheless among the first artists to clearly apply the principles of linear perspective. His work stands at a crossroads: between the decorative sensibility of the medieval tradition and the new science of space promoted by Brunelleschi.

The Foundation of the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore (1423)[22][23]

This panel, painted for the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, depicts Pope Liberius tracing the plan of the church during a miraculous snowfall that, according to tradition, took place in the fifth century. The work was commissioned within the framework of the urban restoration promoted by Pope Martin V after the end of the Avignon Schism.

Masolino arranges the scene with remarkable precision, directing the architectural lines toward a central vanishing point—which many consider the first fully conscious application of this principle in Italian painting. While he retained Gothic features such as elongated figures and ornamental detail, the spatial organization already followed a new logic: that of rationally constructed space.

Commissioned in Rome under Pope Martin V, now housed in the Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

Pope Liberius (likely bearing the features of Martin V) designs the church’s plan during the miraculous snowfall.

This work marks a decisive moment: it shows how perspective began to take hold in painting, not through theory, but through practical observation and a will to order.

Masolino and the Goldman Annunciation (1424)

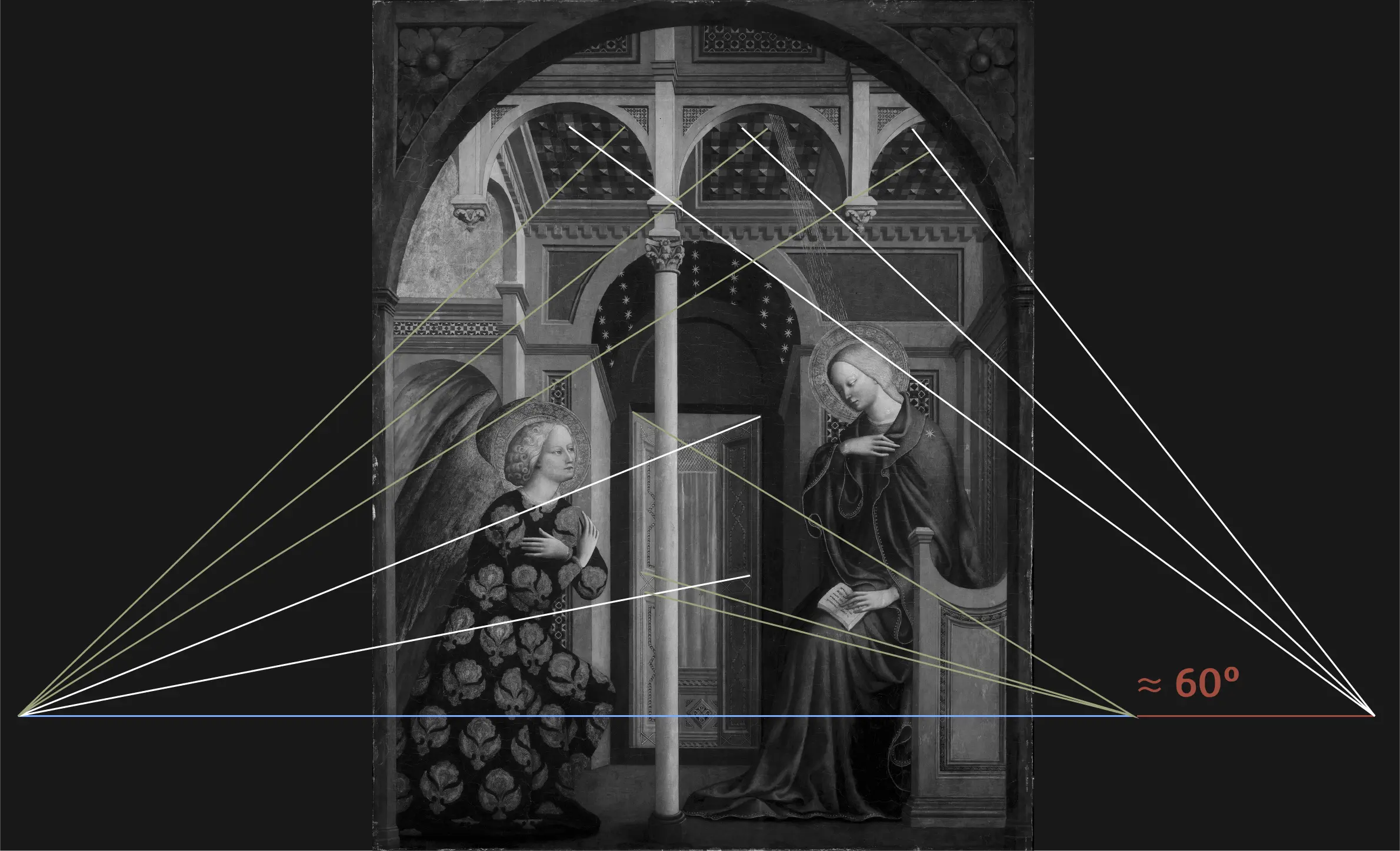

The so-called Goldman Annunciation (1424)[24], now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is one of the most sophisticated experiments in architectural perspective of the early Quattrocento. Its dating is certain thanks to the signature and date inscribed on the original frame, making it a key testimony from the years immediately following Brunelleschi’s experiments.

National Gallery of Art, Washington. Signed and dated on the original frame (from San Niccolò Oltrarno, Florence).

Depth is constructed through the recession of arches, coffers, and doors.

An architecture that opens toward the viewer

Masolino places the vanishing point very low, forcing the viewer to see the scene as if it were located on a higher plane. The architecture is presented frontally, as if observed from the other side of the arch, like a theatrical stage. In doing so, he not only organizes the scene according to the rules of the new perspective but also invites the viewer to peer into an intimate, elevated space—one that unfolds before the eyes as a sacred enclosure accessed visually.

Perspective analysis: the orthogonal lines converge at a very low vanishing point, almost at the Virgin’s feet. This choice emphasizes the frontal openness of the architecture and shifts the focus to the coffered ceiling, which becomes the true demonstrative surface of perspective.

Doesn’t this device recall nativity dioramas, where the viewer looks into an interior scene enclosed on three sides and open on the fourth?

From such a low horizon, including a perspectival floor would have distorted the composition or even made it incoherent. That is why Masolino omits the floor as the main surface and instead makes the coffered ceiling the true support of spatial demonstration. The gaze does not escape downward but rises toward the architecture sheltering the scene, highlighting its sacred dimension. At the visual core—in the very heart of the painting—Masolino introduces a geometric symbol with deep spiritual meaning.

Why place Solomon’s Knot at the vanishing point?

In the Quattrocento, the vanishing point was not a mere technical device: it was the invisible nucleus that organized the entire space. By placing a Solomon’s Knot[25] at that spot, Masolino transforms a mathematical solution into a visible emblem. He does not simply apply the technique—he proclaims it. The geometric center is marked with a symbol that speaks of unity, eternity, and perfection.

At the vanishing point lies a painted Solomon’s Knot on the pavement, turned into an emblem of unity and eternity within the perspectival architecture.

In fifteenth-century Florence, Solomon’s Knot carried multiple meanings: a symbol of wisdom and justice through its biblical associations; a prestigious ornament in coats of arms and textiles; and a geometric figure of perfection in pavements and decorative arts. Masolino introduces it at the visual center of the painting as a sign of harmony between faith, reason, and beauty. He thus fuses symbolic tradition with the new logic of Renaissance space.

Note: This choice makes the work exceptional: no other Quattrocento painter places an allegorical motif so clearly at the vanishing point, with full symbolic intent.

Exceptional geometric precision

Perspective analysis: the 45° diagonals vanish correctly on the horizon line. On the rear doorway, the right panel follows that same angle, while the left panel opens toward nearly 60°, thus vanishing toward a different point. This difference is not an error but the faithful representation of two real angles within the same buildable space.

The 45° diagonals project to distance points on the horizon line, strictly following the logic of central perspective. Even the variations between doors opening at different angles obey a precise geometric coherence, rare in painting of the time. The work demonstrates that Masolino—trained in the International Gothic—understood and applied the new principles of pictorial space with remarkable mastery.

From theory to practice

Can you imagine viewing this panel while aligning the horizon line with your own eye level? It is then that the effect becomes truly spectacular. Brunelleschi had conceived perspective as a scientific system: his panels were precise demonstrations, but not artworks in themselves.

Masolino, by contrast, takes that theory and turns it into a visual and emotional experience. The Goldman Annunciation not only convinces the intellect—it moves the eye. The viewer does not analyze the perspective: they feel it, as if they could “enter” the represented space. This trompe-l’œil*, placed in the service of a sacred narrative, transforms the work into a landmark of Western art.

* The term trompe-l’œil[26] designates a painting that deceives the viewer’s eye, creating the illusion of reality on a flat surface.

Masolino and Masaccio: a dialogue in the Brancacci Chapel

Decorated by Masolino and Masaccio between 1424 and 1428 with scenes from the life of Saint Peter. It has been called the “Sistine Chapel of the Early Renaissance” for its enormous influence on art history.

The patron behind the decoration was Felice Brancacci, a prosperous silk merchant and diplomat in Cairo, who upon returning in 1423 decided to adorn his family chapel in the Church of the Carmine[27]. In 1424 he hired Masolino da Panicale, who at the time was collaborating with the young Masaccio, eighteen years his junior.

Although for a long time it was believed that Masaccio was Masolino’s disciple, today we know that was not the case. Since 1422, Masaccio had been registered as an independent master in the painters’ guild (Arte de’ Medici e Speziali)[28] and was receiving commissions on his own. Several studies suggest that by around 1423 the two shared a common bottega, working more as partners than in a hierarchical relationship. From this collaboration came works such as the Saint Anne Metterza[29] and the fresco cycle on the life of Saint Peter in the Brancacci Chapel.

Their artistic dialogue is defined by one essential aspect: both applied frontal one-point perspective. Yet each did so in his own way. For this reason, in the following scenes we will analyze case by case how each painter organized space. Despite their stylistic differences —Masolino still retained a Gothic flavor, while Masaccio introduced bold monumentality and unprecedented drama— here we will focus exclusively on the use of perspective as a visual tool.

Perspective in Masolino: a convincing yet scattered space

Fresco, 255 × 598 cm (complete fresco).

Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

In the Healing of the Cripple and Raising of Tabitha, Masolino adopts the rules of frontal one-point perspective and succeeds in constructing one of the most coherent urban spaces of his time. The square, façades, and side street follow a well-defined geometric structure. However, the scene feels fragmented: different actions coexist within the same frame, and a multitude of details —hanging objects, animals, passersby— enrich the scene but divert attention. Perspective here functions as a credible stage, but not yet as a narrative language.

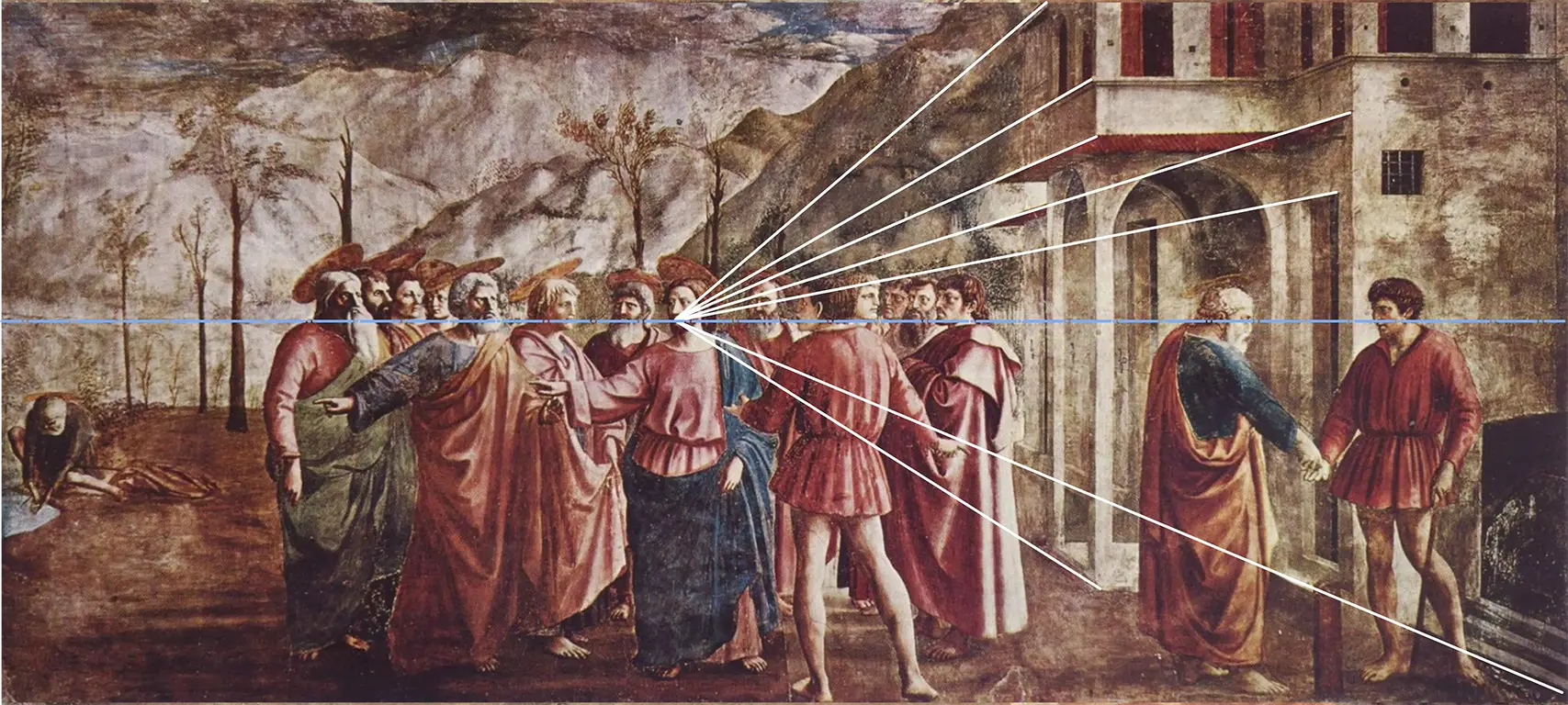

The vanishing point as narrative key in Masaccio

Fresco, 255 × 598 cm (complete fresco).

Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Masaccio, on the other hand, goes a step further. In his famous Tribute Money, the vanishing point becomes the true structural axis of the scene. He places it in none other than the mouth of Christ, from which the Word emerges. Thus the geometric center coincides with the theological center: the entire space —and with it, the whole narrative— revolves around Christ’s teaching. Perspective ceases to be a mere technical support and becomes dramatic language and theological sign.

We can understand this evolution on three complementary levels:

- Perspective as a technical tool: allows the three-dimensional space to be represented with mathematical rigor.

- Perspective as a compositional resource: structures the scene, hierarchizes elements, and guides the gaze.

- Perspective as a symbolic language: concentrates the dramatic or spiritual meaning in a precise point, as Masaccio does by placing the vanishing point in Christ’s mouth.

Brunelleschi had demonstrated the laws of perspective with a rigorous method, but his experiment was still an abstract demonstration. It was not art, but visual science. The true transformation occurred when Masaccio and Masolino brought that system into the realm of visual storytelling.

For them, perspective was not a cold calculation but a way of signifying. It became a narrative structure and the symbolic center of the scene.

Masaccio, in The Tribute Money, underscores the authority of the Word. By placing the vanishing point in the mouth of Christ, he fuses geometric construction with theological message: all visible order rests upon His Word (Verbum Dei).

Masolino, in the Goldman Annunciation, uses the vanishing point as a symbolic sign. By anchoring it in the Solomon’s Knot, he turns mathematical convergence into an emblem of perfection and unity.

Both demonstrate that perspective in the Renaissance was not only an optical achievement but a revolution of meaning. Geometry became language, and the vanishing point evolved from a construction tool into the visual center of thought.

Donatello and the Feast of Herod

The bronze relief of the Feast of Herod (c. 1423–1427)[30][31], created by Donatello (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi)[32] for the baptismal font of the Siena Baptistery[33][34], is a landmark in Renaissance sculpture and in the application of linear perspective. It was his first bronze relief, originally part of a program commissioned from Jacopo della Quercia. Donatello took over this panel after an advance in 1423, completing it in 1427. Later, sculptures of the Virtues were added, including Fides and Spes, also by his hand (1429).

1. The Geometric System

In just 60 × 61 cm, Donatello constructed a convincing three-dimensional space, rigorously applying the principle of one-point perspective. A friend of Brunelleschi, he translated into sculpture the principles that had been formulated in architecture and painting.

Central Vanishing Point

The central vanishing point (in blue) aligns all orthogonals toward the arcade in the background, at the same eye level as the foreground figures (in white). This geometric coherence ensures the illusion of depth in a relief only a few centimeters thick.

Checkered Pavement

The floor grid contracts toward that point, acting as a demonstrative surface of the new spatial system.

Classical Architecture

The semicircular arches, columns, and axial arrangement evoke a Roman interior, modulating depth through the proportional reduction of architectural elements.

2. Perspective and the Stiacciato Technique

Donatello’s genius lay in combining a two-dimensional structure (linear perspective) with a three-dimensional medium (relief). This fusion took shape through the stiacciato[35], a technique that models volumes in decreasing levels of depth:

- Foreground: figures in high relief (Herod, guests, the servant with the head).

- Middle ground: musicians and witnesses, in shallower relief, articulating spatial transition.

- Background: architecture and distant episodes, barely suggested, like a fading vision.

This play of levels allowed the fusion of physical mass and optical illusion, anticipating in sculpture the effects that painting would later achieve through aerial perspective.

Isn’t this essentially the same principle as a nativity diorama with a single focus? A succession of planes: volumetric foreground, modulated middle planes, and an almost evanescent background. Only here, it is not a three-dimensional scenography, but compressed relief with astonishing visual depth.

3. Perspective and Narrative

Donatello does not merely depict space: he uses it as a dramatic tool. Perspective directs the gaze, structures the action, and enhances the story:

- Central Void: the tabletop and floor grid create an open space that draws the eye to the background, contrasting geometric calm with the emotional tension of the foreground.

- Continuous Narrative: two episodes unfold within the same frame: in the background, the execution of John; in the foreground, the delivery of the head and Herod’s reaction. In the middle ground, three figures —one with an instrument— perhaps allude to the festive atmosphere or Salome’s dance. This superimposition of moments, rooted in medieval tradition, here adapts to the rational order of Renaissance space.

The Feast of Herod shows how perspective, far from being a mathematical formula, becomes a visual and narrative tool. First it provides depth, then it structures space, and finally it directs meaning. Donatello does not simply apply a system: he transforms it into art. With him, geometry becomes language, and relief becomes a stage where gaze and meaning converge.

Masaccio and the First Pictorial Application of Perspective

Masaccio (1401–1428)[37] was the first painter to fully apply the laws of perspective discovered by Filippo Brunelleschi to the field of painting. A personal friend of the architect, he is believed to have consulted him when executing his celebrated fresco The Trinity[38] in Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Unlike Giotto or Masolino, who relied on spatial intuition, Masaccio built a pictorial space with mathematical rigor, marking a turning point in the history of Western art.

Fresco, 667 × 317 cm. Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

Considered the first painting to apply the laws of linear perspective with complete accuracy.

1. The Geometric System and the Illusion of Space

Masaccio’s major achievement was to create the illusion of a chapel carved into the wall (trompe-l’œil) through a rigorous perspectival structure. He incised a grid directly into the plaster, applying Brunelleschi’s laws with precision. Even the nails of the cross were drawn with mathematical accuracy.

Vanishing point and viewer’s height: the single point where all orthogonals converge is set at the level of the painted lower step, matching the eye level of an adult standing in the nave. The effect is immersive: the wall disappears, and a deep, believable chapel opens before the viewer.

Architectural construction: the scene unfolds beneath a triumphal arch framing a barrel vault with octagonal coffers, supported by Corinthian columns and Ionic pilasters in pietra serena and white. Every vanishing line responds to an internal structural logic that demonstrates mastery of the linear system.

2. Perspective, Hierarchy, and Theological Meaning

Masaccio transforms perspective into a theological language, organizing the sacred space into a vertical hierarchy of four levels:

- I. The Earthly: a skeleton in a sarcophagus, viewed from above. It is the memento mori: “I once was what you are; what I am, you shall be.”

- II. Humanity Imploring: the kneeling donors, placed at the viewer’s level. They embody prayer and the hope of redemption.

- III. Mediation: the Virgin and St. John, beside the cross, intercede for humankind. They stand within the fictive architecture.

- IV. The Divine: at the deepest point, God the Father supports the crucified Christ, with the Holy Spirit between them. The Trinity becomes the absolute center of spatial and spiritual order.

The perspectival system generates an invisible pyramid that underscores the solidity of dogma: the mathematical order of the universe mirrors the rationality of Christian faith.

3. Perspective as a Language of Faith

The viewer’s gaze ascends from the tomb to the divine, guided by the architecture. Death (represented in the sarcophagus) is not the end, but the beginning of a spiritual ascent toward redemption. Perspective thus becomes a pathway of meaning, not only visual but also symbolic.

The Trinity marks a historical turning point: it is the first major painting where perspective ceased to be a mere technical tool and became a compositional structure and, ultimately, an expressive language. Here, science and faith do not clash but merge: geometry organizes space as a reflection of divine order.

With The Trinity, Renaissance painting could no longer go back: perspective had become an irreversible path. Other painters —such as Fra Angelico, Paolo Uccello, and Piero della Francesca— would take it even further, each in their own way.

Masolino in San Clemente (Rome): the Annunciation on the Entrance Pediment

In the Basilica of San Clemente (Rome)[39][40], Masolino da Panicale was commissioned by Cardinal Branda Castiglioni to decorate the Chapel of St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1427–1430). The cycle includes an Annunciation on the entrance pediment, a Crucifixion on the back wall, scenes of St. Ambrose on the right, and of St. Catherine on the left. On the vault, the four Evangelists and the four Doctors of the Church are depicted.

The ensemble, attributed to Masolino and with no documented participation of Masaccio, marks his mature phase in Rome. The painting reflects a fusion between the late Gothic style and the perspectival innovations he had begun to develop in Florence.

Perspective and Devotional Space

Located on the entrance pediment, the Annunciation functions as a true symbolic threshold. The faithful enter the chapel passing beneath the proclamation of the Incarnation, which makes the scene not only decorative but also a theological doorway: one enters the liturgical space under the sign of the Word made flesh.

From a technical standpoint, Masolino organizes the scene with coherent perspective, applying a system of converging vanishing lines in the architectural frames, cornices, and openings in the background. This spatial structure, already brilliantly tested in the Goldman Annunciation (1424), once again articulates the space as a believable architecture that envelops and situates the figures in a logical and stable setting.

This painting does not introduce dramatic or symbolic elements as striking as the Knot of Solomon in his Florentine work, but it confirms Masolino’s technical mastery in integrating painted architecture and liturgical function. In this case, the scene does not seek to astonish but to accompany: it is a sober and elegant visual greeting that precedes the sacred space as a spiritual antechamber.

The Banquet of Herod: Masolino and Perspective as Protagonist

Baptistery of Castiglione Olona (Varese, Lombardy, Italy).

The vanishing point is located precisely on the central axis, emphasizing the depth of the porticoed walkway.

Perspective as “display”

This fresco is a true scenographic demonstration of the Brunelleschian system. Masolino unfolds a wide porticoed gallery that recedes with geometric rigor into the background. The vanishing point, placed on the central axis, unifies the space and draws the eye toward the horizon, producing a monumental sense of depth.

The architecture is not a mere backdrop, but the visual protagonist: its mathematical precision, the repetition of arches, and the grid of the pavement structure both the depth and the narrative rhythm. The rationality of space imposes its law on the action, turning visual order into a metaphor of temporal order.

Contrast between figure and structure

Against this severe architectural setting, Masolino’s elegant, graceful figures—still tied to the International Gothic taste—move delicately. The contrast between the Renaissance framework and the refined Gothic figures highlights the tension between old and new: the scene is Gothic in form, but Renaissance in its spatial language.

Continuous narration and an ending on the horizon

- Left (foreground): the banquet of Herod, with Salome’s dance.

- Right (foreground): the presentation of the Baptist’s head to Herodias.

- Background (in the mountain): the burial of Saint John, carried out by his disciples.

The scene combines three moments in a single image: a medieval narrative device reinterpreted with Renaissance tools. It is a clear example of what we now call Narrative Art[41], where the visual story unfolds within one pictorial field. Here, perspective becomes a temporal structure: the sequence of episodes aligns with the architectural recession, from the dramatic present of the banquet to the martyr’s final destiny, placed like a distant vignette in the background.

Masolino thus transforms architecture into a narrative path, and the viewer’s gaze becomes a journey: moving from the courtly feast to the silence of the tomb, from worldly spectacle to sacred destiny. Geometry not only creates depth; it introduces a narrative logic that guides the reading and concentrates the meaning of the scene.

Three Echoes to Close a Chapter

Five centuries later, we are still drawing lines, marking vanishing points, and building spaces where the visible points to the invisible. Like Masaccio, Donatello, and the masters of the Quattrocento, the nativity scene artist also seeks a gaze that does not stop at form, but uncovers a deeper meaning behind each plane, each light, and each figure.

The nativity scene is not just a model or a simple Christmas decoration: it is a narrative architecture where perspective, just as in the Renaissance, organizes emotion, guides the gaze, and gives depth to the mystery represented. From the vanishing point to the last light in the background, everything speaks, everything tells a story.

Brunelleschi had his panels; Donatello, his reliefs; Masaccio, his painted chapel. We have cork or plaster, moss or paint, and a worktable that is, in essence, their heir. Materials change, but the gaze seeks the same thing: to give form to the invisible.

The Journey of Perspective in the Quattrocento

From the first experiments in Florence to Alberti’s theoretical codification

1. Before 1435

Perspective as workshop secret

- ✔ Brunelleschi – Experimental panels

- ✔ Masolino – Goldman Annunciation

- ✔ Donatello – Feast of Herod

- ✔ Masaccio – The Trinity

⟶

1435

De pictura

Leon Battista Alberti publishes the first theoretical treatise on perspective

2. After 1435

Perspective as science and symbolic language

- 🕮 Alberti – De pictura

- 📐 Piero della Francesca – Pictorial geometry

- 🌟 Fra Angelico – Devotional space

- 🌀 Paolo Uccello – Visual experimentation

- 📏 Pacioli – Mathematics and proportion

- 🎨 Leonardo da Vinci – Aerial / atmospheric perspective

- 🏛 Raphael – The classical synthesis

References:

- ↑ [1] Renacimiento - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renacimiento

- ↑ [2] Filippo Brunelleschi – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filippo_Brunelleschi

- ↑ [3] Pardo, A. S. (n.d.). PERSPECTIVA LINEAL EN BRUNELLESCHI.

- ↑ [4] File:Masaccio, cappella brancacci, san pietro in cattedra. ritratto di filippo brunelleschi.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Masaccio,_cappella_brancacci,_san_pietro_in_cattedra._ritratto_di_filippo_brunelleschi.jpg

- ↑ [5] Ibn al-Haytham - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 21, 2025, from (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_al-Haytham

- ↑ [6] Book of Optics - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 21, 2025, from (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Optics

- ↑ [7] Roger Bacon – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Bacon

- ↑ [8] Vitello – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitello

- ↑ [9] Lorenzo Ghiberti – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lorenzo_Ghiberti

- ↑ [10] Commentari (Ghiberti) – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commentari_(Ghiberti)

- ↑ [11] An important 13th-century book on optics – Thinking 3D. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://thinking3d.ac.uk/BookonOptics/

- ↑ [12] Baptisterium San Giovanni – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baptisterium_San_Giovanni

- ↑ [13] Piazza della Signoria – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piazza_della_Signoria

- ↑ [14] Antonio Manetti – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Manetti

- ↑ [15] Cupola del Brunelleschi – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupola_del_Brunelleschi#Affreschi

- ↑ [16] Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cattedrale_di_Santa_Maria_del_Fiore

- ↑ [17] Giorgio Vasari – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgio_Vasari

- ↑ [18] The Building of Renaissance Florence: An Economic and Social History - Richard A. Goldthwaite - Google Llibres. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://books.google.es/books/about/The_Building_of_Renaissance_Florence.html?id=O_85aO3wuwoC&redir_esc=y

- ↑ [19] Pintura y vida cotidiana en el Renacimiento - Google Books. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.google.es/books/edition/Pintura_y_vida_cotidiana_en_el_Renacimie/EwNuDwAAQBAJ?hl=ca&gbpv=0

- ↑ [20] Masolino da Panicale – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masolino_da_Panicale

- ↑ [21] International Gothic art in Italy – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Gothic_art_in_Italy

- ↑ [22] Fondazione di Santa Maria Maggiore - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 24, 2025, from (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fondazione_di_Santa_Maria_Maggiore

- ↑ [23] Pala Colonna – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pala_Colonna

- ↑ [24] Annunciation (Masolino) - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annunciation_(Masolino)

- ↑ [25] Solomon’s knot – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomon%27s_knot

- ↑ [26] Trampantojo – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trampantojo

- ↑ [27] Cappella Brancacci – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cappella_Brancacci

- ↑ [28] Arte dei Medici e Speziali (Firenze) – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arte_dei_Medici_e_Speziali_(Firenze)

- ↑ [29] Guarigione dello storpio e resurrezione di Tabita – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guarigione_dello_storpio_e_resurrezione_di_Tabita

- ↑ [30] The Feast of Herod (Donatello) - Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Feast_of_Herod_(Donatello)

- ↑ [31] Donatello’s Feast of Herod. (n.d.). Smarthistory at Khan Academy. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/feast-of-herod.html

- ↑ [32] Donatello – Viquipèdia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donatello

- ↑ [33] File:Baptismal font of the Siena Baptistry la-test battista presenta.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baptismal_font_of_the_Siena_Baptistry_la-test_battista_presenta.jpg

- ↑ [34] Wirtz, R. C. . (2000). Donatello, 1386-1466. 120.

- ↑ [35] Stiacciato – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stiacciato

- ↑ [36] File:Masaccio Self Portrait.jpg - Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Masaccio_Self_Portrait.jpg

- ↑ [37] Masaccio – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masaccio

- ↑ [38] Trinità (Masaccio) – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinità_(Masaccio)

- ↑ [39] Masolino a Roma con il Cardinale Branda Castiglioni | La bottega del pittore. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://blogosfera.varesenews.it/la-bottega-del-pittore/2012/05/31/masolino-a-roma-con-il-cardinale-branda-castiglioni/

- ↑ [40] The Cappella Castiglione in the Church of San Clemente in Rome - Walks in Rome (Est. 2001). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.walksinrome.com/the-cappella-castiglione-in-the-church-of-san-clemente-in-rome.html