Confusion or nonsense? A real case from a Spanish nativity forum

Confusion or nonsense? A real case from a Spanish nativity forum

The posts are like a series:

iif you miss the first chapter or skip the order, you’ll lose the thread 🧵

The following case refers to a Spanish-language nativity-scene forum, where terminology influences how creators are seen. Even if you’ve never visited it, this example shows how language can either erase or affirm artistic authorship across cultures.

These confusions affect how we name things—and how we understand them. Later, I’ll share my personal experience, along with the contradiction this presents when compared to what actually happens at the International Nativity Scene Fair.

For years, I’ve observed how a well-known Spanish-language nativity scene forum repeats certain misunderstandings that go beyond simple terminological disagreement. These are confusions that affect how we name things—and therefore how we understand them.

On this forum, you’ll find titles like:

- Index of Artisan Figurists

- Index of Classical Artisan Figurists

- Index of Foreign Artisan Figurists

The intention may be good: to gather information and share it. But both the language and the system used to sort and display that information are far from neutral, and they directly influence how creators are valued —or made invisible.

But what’s going on?

Misnaming is also erasing

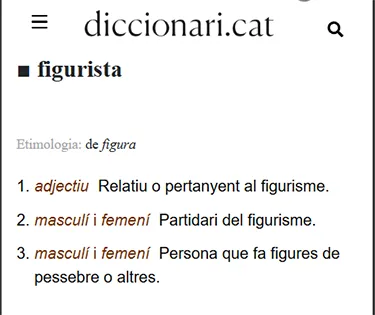

What is a “figurista”? What does that word even mean? Not even the Royal Spanish Academy recognizes it. It’s a term that doesn’t officially exist, used by no one outside the worlds of nativity scenes or model making —except perhaps in Catalan, with a different nuance—, and it seems to have been coined to avoid calling the sculptor by their real name.

Let’s be clear: who makes nativity figures or other types? The churro vendor, the lawyer... or the sculptor?

Why is it so hard to write sculptor who creates nativity figures or other types? Is it really that difficult?

With a single invented word, a double effect is achieved: it avoids calling someone an “artist” and dilutes authorship. People talk about “figurine artisans” as if they were mere manufacturers of stickers, trading cards, toy soldiers or action figures. As if sculpting were a repetitive task, without soul or signature. Like making churros… but “artisanal”.

And this is no minor issue. If we represent the birth of the One who came to bring justice, wouldn’t it be fair to start by naming things properly? Doesn’t the sculptor —who shapes with hands and vision— deserve to be named accurately, without euphemisms or downgrades?

Think about it: without sculptors, there are no nativity figures. There may be producers —that is, artisans— but they remain on hold: without a work to replicate. Because before any copy, there is an original. And without figures, there is no nativity scene. The sculptor is the first link in the nativity chain, and for that reason, their authorship deserves full respect.

A clear example: a sculptor models an original figure in clay or modeling wax, and a workshop produces series copies using molds. They might paint or adjust finishes, but authorship still belongs to the sculptor. This model has long been used in many workshops —especially in Olot or Murcia— where producers are not authors but multipliers of someone else’s creation.

When an “index” isn’t what it seems

The word “index” suggests a neutral list, ordered by objective criteria (alphabetical, chronological, geographical). But on the forum, all it takes is for a client or enthusiast to leave a comment, and a name moves up or down. This turns the supposed “index” into a display susceptible to manipulation: the top positions get more clicks (just like on Google), while names buried on later pages become virtually invisible to the average viewer.

Let’s be honest: all the names that appear in those “indexes” —except the historical ones— pursue two main goals: making a living from their work and building their personal brand. Like any self-employed professional… or freelancer, if you prefer. Because today, if you don’t position yourself, you don’t exist for the client; and if you don’t sell, you don’t eat. As simple as that.

Do you still think it’s neutral?

If you were the one listed on the last page of the “index,” you probably wouldn’t see it as neutral.

Language shapes reality.

When we misuse it, we also take sides. That’s why this manual insists on naming things precisely: the first step toward valuing a work is to respect its creator; this is called empathy. And that empathy extends to all who contribute creativity to the nativity scene —the one who sculpts the figures, the one who designs the setting, the one who creates each accessory— because each adds authorship. However, I reserve the word “creator” for those who truly originate something; owning a collection, no matter how valuable, is not the same as creating — it is simply possessing.

In the next chapter, I’ll explore this legal and moral respect that protects original works. You may be surprised by how much depends on fair and accurate naming.

But really—who would come up with such nonsense?

“Index of Classical Artisan Figurists”

All of them are renowned sculptors, with recognized careers in nativity art and religious sculpture. And yet, the forum places them under the generic label “artisans”.

We see the same terminological flaw again: it’s called an “index,” but there’s no objective order. A collector just needs to reactivate a thread, and a name rises or falls in the list. What’s more, the term “classical” is also misleading. If it's about style, we find classical sculptors in the other two lists as well; if it's about chronology, “historical” or “deceased” would suffice. As it stands, the label confuses: it mixes canonical masters with other names simply due to age, without any clarified criteria.

As for the term “figurists”, we set it aside for its vagueness, imprecision, and lack of definition. It does not accurately or fairly name someone who creates figures with artistic, technical, and symbolic intent.

This is just a small sample of the 56 names included in the so-called “Index of Classical Artisan Figurists” from the belenismo.net forum—names that actually belong to reference sculptors in nativity art history:

- Luisa Ignacia Roldán “La Roldana” (1652–1706) – Andalusian Baroque sculptor. The first woman officially registered as a sculptor at the Spanish court. Appointed Court Sculptor by King Charles II — the highest official recognition.

- Francisco Salzillo (1707–1783) – Considered the most representative 18th-century sculptor in Spain and a key figure of the Baroque.

- Ramón Amadeu i Grau (1745–1821) – Catalan sculptor known for religious and nativity figures.

- Damià Campeny i Estrany (1771–1855) – Neoclassical Catalan sculptor. Professor at the Escola de Llotja in Barcelona.

- Domènec Talarn i Ribot (1812–1902) – Nativity sculptor and academic. Renowned for his religious works.

- Lluís Carratalà i Vila (1862–1937) – Modernist sculptor, actor, and nativity artist. Received the Creu de Sant Jordi for his contribution to nativity art.

- And the next 50.

This is a small sample from the so-called “Index of Classic Figurine Craftsmen” on the belenismo.net forum, where historical figures are grouped who were in fact renowned sculptors. Their works are studied today in museums and art history manuals.

Is more evidence needed? This brief selection is enough to show how incoherent —and culturally damaging— it is to call “craftsmen” those who were widely recognized as sculptors for their technique, artistry, and legacy.

Applying the term “craftsman” to artists like Luisa Roldán, Francisco Salzillo, or Damià Campeny —all unanimously acknowledged as leading sculptors in the history of Spanish art— is a historical and conceptual mistake. There’s no nativity-scene jargon or justification that can excuse it. Culturally, the moderators discredit themselves: such a lapse is indefensible.

Insider Jargon Cannot Rewrite History: A community may create its own terms to describe current practices or members. But that jargon loses all validity when applied retroactively to canonical figures in art history in ways that contradict academic and cultural consensus. It would be as absurd as if a club of book collectors —who have never written a novel— created an “Index of Classic Copyists” to refer to Cervantes, Shakespeare, or Gabriel García Márquez. It might fit their inner jargon... but not historical truth.

Perhaps it would be worth revisiting the classification of ‘Classic Figurine Artisans’

A detail you may not know:

In UNESCO’s Framework for Cultural Statistics (FCS, 2009), there is a cultural domain titled “Visual Arts and Crafts”. At first glance, it may seem like a single category… but it isn’t. The fact that UNESCO mentions them together but separately suggests an important conceptual distinction.

Why are they not the same?

Although both involve creativity, technical skill, and cultural expression, there are key differences in function, context, and perception:

- Purpose:

- A sculpture can be a unique piece, created with an aesthetic, symbolic, or conceptual intention.

- A craft, such as a vase or a basket, usually has a functional use, even if it is also decorative.

- A sculpted or modeled figure doesn’t become art “depending on the context.” It is born as an artistic work, because its expressive intent is present from the very first gesture. Calling it a craft is to ignore its sculptural nature.

- Creation context:

- Visual arts usually have individual authorship (the artist).

- Crafts are more closely tied to collective traditions and knowledge passed down through generations.

- Institutional perception and treatment:

- In terms of cultural policies, statistics, or the art market, sculpture is associated with the Fine Arts, while craft is more often linked to so-called “applied” or “minor” arts in certain institutional contexts.

So then…

If UNESCO itself makes this distinction, why do we keep lumping everything involving hands, clay, or tradition under the label of “craft”?

What’s traditional about silicone, resins, or 3D modeling?

Do we really want to keep calling someone a “craftsman” who works with new technologies, signs their work, and is the author of original sculptures?

Since when does a figure of the Baby Jesus “serve a purpose”? It’s not a useful object — it’s a meaningful creation. It is contemplated, venerated… and above all, the original sculpture is created with intention. Because today, a machine alone can handle reproduction — and, if you push it, even the painting.

So… where does that leave the craftsman? Where are the “exécutants”, the executors?

Do you really need a craftsman for that? Or is it enough to press “print,” “paint” … and let the machine do the job?

But… what’s really going on?

There is a fundamental distinction between the sculptor who conceives the original work and the executing artisan who reproduces it. The sculptor contributes creative vision, intention, and a unique design, infusing the figure with profound meaning that reflects its cultural, spiritual, or artistic context.

The executing artisan, on the other hand, is responsible for materializing that vision, whether through traditional techniques or with the aid of modern tools such as mechanical reproduction.

Even in reproduction, the artisan is not merely an operator. Their ability to interpret the original work, preserve its essence, and ensure its quality remains essential. A machine may replicate forms with precision, but it lacks the sensitivity to capture nuance or adjust details. The finish, the care in gestures, the adaptation to specific materials… all of this requires human judgment. The machine executes; the artisan interprets.

The danger lies in reducing the artisan to a mere button-pusher. If reproduction becomes fully automated, we lose the human value of craftsmanship: the connection to tradition, the respect for the original work, and the ability to breathe life into every copy. In this sense, the executing artisan remains essential — so that a reproduction is not just a hollow copy, but a soulful extension of the original meaning.

From Artisan to Artist: A Long-standing Struggle for Recognition

For centuries, sculptors, painters, and builders were considered mere artisans: anonymous executors working under religious or noble commissions. But during the Renaissance —especially from the Italian Quattrocento (1350–1464)— things began to change.

Figures such as Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Leon Battista Alberti argued that art was not only about making, but also about thinking, inventing, composing. They claimed that a sculptor should be recognized as an intellectual creator, not merely a manual executor. This marked the birth of the modern concept of artist.

Source: De Pictura, Leon Battista Alberti (1435). General history of European art. The Florentine School and the birth of the artist-author.

And today, 675 years later, are we still calling “artisan” the one who conceives and sculpts an original figure for the nativity scene?

...!?

Because all the names included in those “indexes” —without exception— have created the original figures from their own artistic background. And that makes an essential difference: production or reproduction is not the same as creation.

In sculpture, there are two clearly distinct roles: the author and the executor.

Calling the former an “artisan” is a terminological injustice that confuses creation with copying, and erases what matters most: authorship.

Maybe the problem is not the sculptor, but those who haven't understood that language has consequences.

Or perhaps they have understood… and that’s why they use it this way?

That’s called subconscious manipulation.

A Glimpse of Reality: the Missing Word

In theoretical debates, it may seem like a semantic issue. But in practice, those who create nativity figures have already chosen how they present themselves to the public. Just look at the official posters from the 2025 International Nativity Fair (10th edition):

“Artistas”

Gianfranco Cupelli y Peter Rock

Amantea (Italia)

“Arte Presepiale”

Michele Buonincontro

Nápoles (Italia)

“Artista”

Fabio Squatrito

Misterbianco-Catania (Italia)

“Original”

Heide

Laion (Italia)

“Scultore”

Federico Iaccarino (Italia)

“Artista”

De Francesco

Nápoles

“Artista”

Emili Solé Carcolé

Riudaura (Gerona)

“Arte belenista”

Cristina Domínguez (Cádiz)

“Arte Belenista”

F. Javier Martín

Navalcán (Toledo)

“Sucesor de Ángel”

Martínez

El Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz)

“Arte Belenista”

Javier Aniorte

Callosa de Segura (Alicante)

“Artesanía”

Guilloto

El Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz)

“Complementos”

José Cruz

Córdoba

“Artistas”

El Portalico de Belén

El Altet (Alicante)

“Artistas”

Córdoba

“Creando Arte y Tradición Higinio”

Villarrobledo (Albacete)

“Escultor”

José Luis Mas

La Eliana (Valencia)

“Escultor”

Fran Carrillo

Totana (Murcia)

“Complementos”

Barsua 3D

La Palma del Condado (Huelva)

“Complementos”

Joaquina Hurtado

Lucena (Córdoba)

“Artesanía”

Mirete

Ceutí (Murcia)

“Arte Belenista”

Pepe Domínguez Miranda

Jerez de la Frontera (Cádiz)

“Complementos”

Riofrío

Alovera (Guadalajara)

“Artista”

Rubén Galindo

Sevilla

“Complementos”

Las Cosas de Vivi

Huesca

“Complementos”

Mibako Miniaturas

Valladolid

“Artistas”

Creaciones Tula

Pamplona

“Belenes Angeles Camara”

Juan Giner

Alicante

“Figuras Belenes”

Ángeles Cámara

Callosa de Segura (Alicante)

“Creaciones Artísticas”

Daimon

Piera (Barcelona)

“Napolitanos”

Vázquez & Luna

Medina-Sidonia (Cádiz)

“Animales de Barro”

Granada

“Arte Belenista”

Venezzola

Melide (La Coruña)

“Complementos”

FMAS Automatización

Montilla (Córdoba)

“Alfares”

Sevilla

“Pintor”

Reza Baharlou

Palencia

“Arte Sacro”

Hermanos Cerrada

Los Palacios (Sevilla)

“Escultora”

Montserrat Ribes

Càstellar del Vallès (Barcelona)

Why is it so hard to say “sculptor”?

Giving something its name seems easy… until it becomes uncomfortable. And in this case, saying “sculptor” seems to raise more resistance than one might expect. Why does it happen? What is being avoided? To understand it better, I suggest a short exercise: let’s briefly step into the shoes of three different profiles that might offer clues about this reluctance to use the word.

Seen in this light, perhaps what is being avoided isn’t the word itself, but what that word reveals: authorship. And when the author is made invisible, neutrality isn’t gained. Truth is lost.

When calling things by their rightful name becomes uncomfortable

When calling things by their rightful name becomes uncomfortable

I was an active member of that forum for years. I participated respectfully, shared knowledge, and at one point, I made a simple suggestion: that the so-called “Artisan Figurists” be renamed “Nativity Scene Sculptors”. My proposal wasn’t an imposition but a call for consistency. If we’re talking about art and original creation, the fair term is sculptor. But the reply was blunt: “You’re confused.” I was told “figurist” and “artisan” were the right words. No reasoning — just the authority of habit.

Who decides those words? With what authority? And with what consequences?

In recent years, the forum had turned into a constant string of contradictions: you offer all kinds of detailed explanations, and all you get in return is indifference, disdain, or outright dismissal. There’s no real debate, no counterarguments—just labels, empty qualifiers, and little else. That’s why I say that forum became the exact antithesis of what I explain in this manual, and staying there would have been an impossible contradiction to accept. The glass overflowed when I saw that the forum’s inertia protected violations of its own rules and allowed blatant devaluation of other people’s work. When not a drop but a stream fell into a glass already full, I decided to leave and pack my bags—because that’s my baggage as an artist.

Apparently, that gesture was unforgivable: it only took two personal, baseless comments to appear. Classic style: ruthless personal attack. Opinions without arguments. Judgments without understanding. Empty words, lacking ethics or foundation. Fallacies dressed up with sentiment to persuade. —And a few took the poisoned bait and applauded with a “like.”—

My two detractors revealed themselves as pretenders—self-proclaimed art experts with no grasp of what it means to be a sculptor today. With empty eloquence, they tried to judge what they do not understand — including my own decision. Their uninformed judgments, those empty and fallacious words wrapped in sentimentality, were nothing more than the reflection of a pretense meant to disguise their lack of understanding and their resistance to any change that challenges the status quo. Deep down, their “offense” wasn’t about legitimate disagreement, but about the loss of a resource that would no longer serve them, the loss of a voice that called out their comfortable mediocrity. It was also a clear act of cowardice—taking advantage of my absence to avoid a face-to-face exchange or a reasoned debate. Does my legitimate decision to leave require any permission or further explanation?

Setting boundaries is an inalienable right of every individual—a way to protect one’s personal space, time, energy, and mental well-being.

No, I will not mention their names or respond in kind. I don’t believe in attacking someone in their absence, as they did. I prefer to explain the facts with arguments, not with empty insults.

And if I explain it here, in this manual, it’s not to strike back, but to expose a serious mistake: misnaming and disrespecting the sculptor’s work.

Then I asked myself: can’t someone leave simply because they disagree?

As if walking away had become a serious offense worthy of punishment!

I understood it immediately after reading the comments: it wasn’t just disagreement — it was loss. The loss of someone who contributed content and would no longer feed a forum grown stale in both form and discourse.

But if any of them is reading me today, I’d like to say something sincerely: thank you. Thank you for valuing me enough to devote your time to me. Few things say more about a work than the stir it causes when it unsettles what’s already established.

What sense would it make to remain listed in an “Index of Artisan Figurists” that denies the authorship I defend on every page of this manual?

Must one be hypocritical, cynical, or incoherent just to please a few…?

If you’re looking for me, you won’t find me on the forum. Clearly, I was right to invoke intellectual property law.

Fair winds and a new sail!

To keep creating and name what is born justly, in another harbor, may be the best way forward

To name justly is to respect

When it comes to professional identity, using the most common term is not enough: we must use the fairest one, the one that truly reflects the work someone does.

When a sculptor says, “I’m not a craftsman, I’m an artist, I’m the author of my works,” and is still labeled as a “craft figure maker”, we are not being neutral. We are erasing their voice with our own.

This violates a basic principle of respect and justice: letting each person say who they are.

What if we started by naming justly those who shape the Nativity with their own hands?

This isn’t just a terminological confusion. Some, from their role as moderators or passionate collectors, end up shaping the narrative of nativity art to fit their own view. They haven’t studied Fine Arts or Art History, because art is studied, updated, revised, and reflected upon. Even so, they claim the right to define those who actually create: the true sculptors, artists, authors.

This is where the real problem appears: when someone who does not create figures tries to impose the identity of the one who does create the most essential part of the nativity —the figures—, the conflict is not just semantic: it is a wrongful appropriation of the creator’s voice. A clear example is the deception of the so-called “patina effect,” a fiction that tries to assign authorship of a figure to the collector just for commissioning it, reducing the sculptor to a mere executor. This is a clear sign of egocentrism, denying the real creative process and the artistic background of the author.

It's a necessary reminder: in any artistic field, the voice of those who create should take precedence over those who, while passionate, are not directly involved in the creative process. This doesn’t mean denying the value of collectors or moderators, but it does mean remembering that their perspective should not override that of the artists.

And it’s worth repeating, even for the most skeptical: without artists, there are no figures… and without figures, there is no nativity scene, no collection, and no forum to moderate.

Because without figures, there is no nativity scene. There may be landscape, there may be scenery… but there is no story to tell.

Intangible Heritage: The Crown of Incoherence?

We’ve shown here how using precise terms is a fundamental act of respect. But what happens when the very declaration of cultural heritage hides the truth? There is a moral and conceptual contradiction at the heart of this official recognition—one few are aware of, and that we now invite you to uncover. Get ready to discover a side of nativity art you’ve probably never been told about.