The Amades Case: The Mystery of the Omissions

The Amades Case: The Mystery of the Omissions

The posts are like a series:

if you miss the first chapter or skip the order, you’ll lose the thread 🧵

Prologue: The Mystery of the Omissions

In 1946, Joan Amades wrote his famous definition of the nativity scene, which was later accepted at the Second International Nativity Congress in Rome in 1955. [1] However, when examined closely, it reveals significant omissions. It seems Mr. Amades left some clues, but missed key elements.

Was it due to ignorance?

To a partial view of nativity tradition?

Or simply because those aspects didn't interest him?

Elementary, dear reader — let’s examine each hidden piece in this puzzle.

Clue 1: The Artistic Diorama… A Case Unknown to Amades?

In his definition, Amades describes the nativity scene as a “plastic and objective representation of the birth of Jesus in a panoramic landscape.” But he never mentions the “nativity dioramas” or L'Escola de Barcelona del pessebrisme, which had existed in Catalonia since the early 20th century (1912). [2]

The “panoramic landscape” is no oversight, but the core of his definition.

Amades describes the nativity as an open landscape, visible “a vista d’ocell” (bird’s-eye view). With this phrase, he sought to narrow the scope of his ethnographic study and exclude altarpieces, church displays, or “window-box dioramas” from the popular corpus he focused on. In this sense, the single-frame diorama was ex profeso excluded — not because he was unaware of it, but because it broke the panoramic view he considered essential. According to his definition, then, it cannot be classified as a nativity scene. Hmm…!

El Pessebre is, above all, an ethnographic monograph, not a technical scenography manual. Its aim was to document popular customs and symbols on a Catalan scale, not to catalogue every material innovation. This bias explains several “omissions” without assuming bad faith or ignorance.

To an ethnographer focused on descriptive cultural studies — especially in its popular forms — the diorama could seem like a 'school-based' or 'artist-driven' innovation, not one born from the people. This is because the diorama is more theatrical, technical, and displayed mostly in galleries.

These dioramas required carefully planned lighting, specialized materials, etc. All of this distanced them from the “popular” — in the sense of something emerging spontaneously from the people, without prior technical training.

Joan Amades didn’t “forget” the diorama; he simply viewed it as something different from the nativity scene that he wanted to preserve as a living, evolving, and popular tradition.

Case details:

Antoni Moliné i Sibil (1881–1963) developed the artistic diorama in 1912 in Barcelona, with a concept radically different from the traditional nativity scene. Instead of an open display visible from multiple angles, he limited the view to a single point, using theatrical perspective and plaster techniques to achieve a more realistic effect. This marked the birth of the closed nativity scene or single-frame composition.

By the time Amades wrote his definition (1935), the artistic diorama—or what would become known as L'Escola de Barcelona del pessebrisme—had already been evolving for 23 years and was recognized in the Spanish nativity scene world.

🖈 But in his definition, Amades makes no mention of it. Hmm...!

Theories:

- Lack of knowledge: Could a folklorist and ethnographer from Barcelona really have been unaware of a nativity innovation born in his own city? Unlikely, but not impossible.

- Lack of interest: Amades had a strong inclination toward popular and traditional culture. He may not have considered the diorama a genuinely folkloric expression.

- Historicist bias: Perhaps his view focused more on what the nativity had historically been, rather than on its recent transformations.

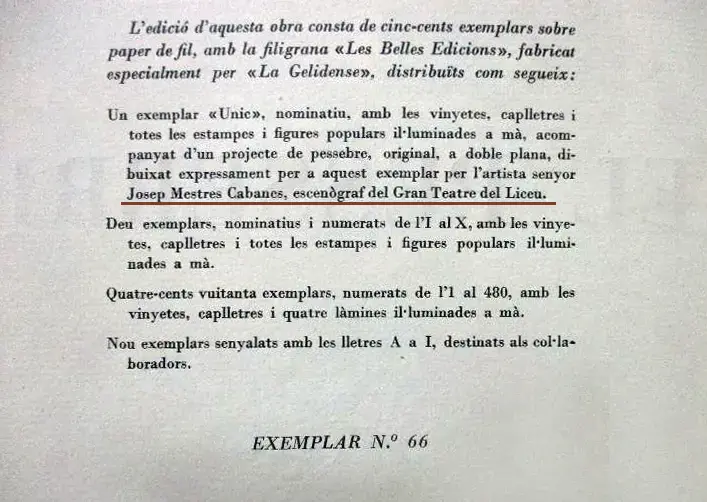

The fact that Josep Mestres i Cabanes, a renowned painter, scenographer of the Gran Teatre del Liceu and professor of perspective at the Escola Superior Sant Jordi in Barcelona, was involved in the first edition of Amades’ book and yet the diorama is absent from both the 1946 definition and the 1959 edition update, reinforces the idea that this was not an exhaustive classification of nativity scene styles, but rather a partial view shaped by Amades’ own criteria.

Contextual analysis: Amades’ close relationship with Josep Mestres i Cabanes —professor of perspective and nativity enthusiast— combined with the dissemination of Antoni Moliné’s dioramas in Barcelona since 1912, makes it highly unlikely that Amades was unaware of this innovation. Everything points to a deliberate exclusion: his definition prioritizes the popular “panoramic” nativity scene he wanted to define for ethnographic purposes. The diorama, more theatrical and framed from a single viewpoint, did not fit that conceptual framework.

Note.

Joan Amades died in Barcelona on January 17, 1959, just a few weeks after seeing the third edition of El Pessebre printed; therefore, he was unable to incorporate later changes or respond to innovations that came after his death.

Whatever the reason, his omission left out one of the most important technical innovations in nativity scene history.

Clue 2: Plaster and modern technique… A crime against innovation?

In his description of the nativity scene, Amades does not mention the materials with which the "artistic nativity" should be built. However, his definition suggests a preference for nativity scenes made using traditional techniques, which excludes a key innovation: the use of plaster in nativity scene construction. It’s not that plaster suddenly appeared; it had already been used in sculpture since the Predynastic period, around 3,000 B.C., in Egypt.

Case facts:

- Until the early 20th century, nativity scenes were built using materials like cork, wood, or papier-mâché. Fine sand, crushed cork, or sawdust were used for the ground, and moss, lichens, branches, etc., for vegetation.

- In 1912, Antoni Moliné introduced the use of plaster in nativity art, allowing for greater realism and detail.

- Amades does not mention this innovation at any point, which suggests he either did not consider it relevant or simply disregarded it.

Why does it matter?

Because the use of plaster enabled the development of dioramas and a more detailed, realistic style of nativity art. To omit it is to ignore one of the most important shifts in nativity scene construction and the now famous “Barcelona School of Nativity Art”.

Clue 3: The Living Nativity… A case beyond his time?

Another major omission in his definition is the living nativity scene, the dramatized reenactment of the nativity.

Case facts:

1. The first documented living nativity scene took place in Bojano in 1951 (Molise region, Italy), five years after the 1946 edition of his book. It is very likely that Amades was completely unaware of this event.

“Una manifestazione che si può considerare tra le prime espressioni del presepe vivente in Molise si tenne a Bojano nel 1951, con la partecipazione di figuranti provenienti da Guardiaregia e San Polo Matese”

2. The second documented living nativity scene took place in Engordany in 1955 (Andorra), a few years after the 1946 edition was published. However, it was not mentioned in the 1959 edition either.

In this case, it is almost certain that he was aware of it, since the book El Pessebre d’Engordany was published just a year before his death. The revealing detail is that it was published by Editorial Barcino itself, as part of its collection Biblioteca Folklòrica Barcino (Volume XVI). For a folklorist from Barcelona, it would have been nearly impossible to overlook this work. It is hard to understand, unless his state of health prevented him from addressing it, as he died shortly after the third edition was printed. Even so, there is no known explicit reason to justify this omission within his folkloric framework.

3. The tradition of representing biblical scenes with actors was not new, but the format of the living nativity scene became established in the second half of the 20th century.

4. Today (2025), there are 49 living nativity scenes in Catalonia, more than the 46 Catalan nativity scene associations.

—According to the Federació de Pessebres Vivents de Catalunya, in the 2024–2025 season there are 49 living nativity scenes throughout Catalonia—. [7]

Can we blame Amades for this omission?

Not entirely. In 1935, when he wrote his definition, the living nativity scene had not yet become popular. However, his view of the nativity was so narrow that it left no room for new forms of expression. If his definition had been more open, it might have evolved over time instead of becoming completely outdated.

Provisional Conclusion: A Framework Too Rigid

If we examine Amades' definition through Sherlock Holmes’ magnifying glass, we find that:

It doesn’t mention the artistic diorama or L'Escola de Barcelona del pessebrisme, even though they had existed in his own city for over 47 years by the time of the 1959 edition.

It ignores the use of plaster, even though this technique had already revolutionized nativity scene construction.

It doesn’t consider the living nativity, since it wasn’t yet widespread, but his definition also left no room for future innovation.

This leads us to a first hypothesis: Amades built a rigid definition, shaped by his time and traditionalist perspective. Perhaps unknowingly, he closed the door on new forms of nativity scene expression that were already emerging.

Complementary Note:

This rigidity also excludes living and symbolic forms of nativity tradition that, although developed later, are now part of the Catalan popular imagination. A significant example is the placement of nativity scenes on mountaintops, a tradition documented in Catalonia since the mid-20th century. Every Christmas, hiking groups climb emblematic peaks such as Montcau, La Mola, or Matagalls to set up a small nativity scene at the summit, often accompanied by songs, Gospel readings, and community celebration. This practice, which blends landscape, spirituality, and folk culture, is further proof of how the nativity adapts to new symbolic settings outside the traditional panoramic framework. [8]

“On December 13, the placement of the Pessebre dels Muntanyencs will take place at the summit of Les Agudes, the highest point of the Montseny range. As is now traditional, this will be the fourteenth edition (1956); the nativity will be carried by foot from Barcelona…” [9] Tele exprés (December 8, 1970, pp. 15)

Nativity on the Peaks: “Go and proclaim it from the mountain”

“The tradition of setting up the Nativity on mountaintops began in Asturias and León in the 1940s and 1950s.” [10]

📣 The origin of the confusion: a misinterpreted text

The idea that nativity scenes are divided into ‘artistic’ and ‘popular’ categories comes from a text by the ethnographer Joan Amades in his book El Pessebre (1946). However, what few people mention is that in the same book, Amades clearly stated that every nativity scene is a work of art; in fact, in chapter X he says:

❝Chapter X

NATIVITY SCENE TRADITION

Building a nativity scene is an art form, no matter how small or humble, yet an art form nonetheless, imbued with emotion and sensitivity—the foundation of any true artistic work no matter how insignificant it may seem. Without these, art cannot exist. And art is expansive; if it were not, it would cease to be art and would only appear to be. As a result of this natural expansiveness, one feels the need to share that personal emotion with others, and experiences the joy of creating a nativity scene both for the intimate satisfaction of making it and the pleasure of displaying it.

The act of building a nativity scene and the customs surrounding its creation and display have given rise to an ethnological phenomenon referred to as "belenismo"—a term under which we intend to explore the nativity scene as a tradition and everything that surrounds it in that sense.

The artists who create nativity scenes have been called “belenistas,” a term already in use in 1805 in reference to the woodcarver and cabinetmaker Ramón Beguer, who created a public nativity scene to uplift people’s spirits during Christmas of that year, when the city was under the heavy shadow of grief due to the Napoleonic invasion. ...”

Bibliographic note. The quoted excerpt is from Joan Amades, El Pessebre, Barcelona, Editorial Aedos, 3rd revised edition, 1959, chap. X, p. 413. The first version appeared in Les Belles Edicions, 1935, with slight variations in the wording of the prologue.

Context note. Joan Amades passed away in Barcelona on January 17, 1959, just weeks after seeing the third edition of El Pessebre printed; therefore, he was unable to make any updates or respond to innovations that appeared after his death.

In other words, Amades claimed that every nativity scene is a work of art, no matter how humble it may be.

How Did the Confusion Arise?

The problem began when part of his book was taken out of context and repeated as if it were an absolute rule.

In the introduction, Amades describes two ways of making the nativity scene in his time:

Artistic nativity scene: “Made by people with artistic knowledge, concerned with historical and pictorial accuracy.”

Popular nativity scene: “Created by ordinary people, with a strong traditional and emotional component, but without academic intent.”

Amades operated within a strongly ethnographic-popular mindset, not inclined toward technical experimentation.

He was merely describing a reality of his time, but over the years, this classification has been misunderstood. People started to mistakenly believe that:

❌ The “artistic” one was superior because it was made by experts.

❌ The “popular” one wasn’t art, but merely a tradition with no artistic value.

This interpretation stems from a partial and shallow reading of Amades’ book.

Those who have read the full work and understand the author's approach will likely see his classification in the introduction from a different perspective.

If this confusion didn’t exist, there would be no need to explain it. However, it originates from an incomplete reading of the book, repeated so often that it eventually became accepted as unquestionable truth.

Copying and Pasting Without Context: The Risk of Distorting the Truth

In the information age, verifying data is more crucial than ever. As a sculptor and content creator, I strive to provide the most accurate and reliable information possible, based on rigorous sources. However, it's important to remember that despite our best efforts, we are all prone to making mistakes or misinterpreting the vast amount of available information. That’s why I encourage my readers not to take this (or any other) content at face value without their own verification and critical thinking.

The Myth: The "Bethelem Ban" of 1601

An example that highlights the importance of checking historical facts.

In today’s “copy and paste” culture, repeating a quote out of its original context can lead to historical distortions. One striking example is the alleged “Bethlehem Ban” issued in England in 1601, which —according to certain blogs and even the Spanish Wikipedia article on «Belenismo»— supposedly ordered the burning of nativity figurines and the death penalty for those who kept them.

Original

“Cuando Inglaterra adoptó el anglicanismo, las figuritas belenistas fueron quemadas, y debido al rechazo a los íconos, en 1601 se hizo un decreto, la "Bethelem Ban", y quien no lo cumpliera sería condenado a muerte; en el siglo XIX con la consolidación de la tolerancia religiosa, se levantó esa condena.”

From: catholic.net/¿Qué es el belenismo?

“copy and paste”

“Cuando Inglaterra adoptó el anglicanismo, las figuritas belenistas fueron quemadas, y debido al rechazo a los íconos, en 1601 se hizo un decreto, la Bethelem Ban,[10] y quien no lo cumpliera sería condenado a muerte; en el siglo XIX, con la consolidación de la tolerancia religiosa, se levantó esa condena.”

From: Wikipedia/Belenismo

This is a serious historical inaccuracy, given the severity of the accusation and the complete lack of evidence to support it.

1. Absence of a “Bethelem Ban” in 1601:

There is no historical evidence or academic bibliography that supports the existence of a specific decree called the “Bethelem Ban” in 1601 that imposed the death penalty for possessing or displaying nativity figures. Historians specializing in the English Reformation and the history of Christmas make no mention of such a law. If a law of such magnitude—involving the death penalty—had ever been debated or approved, it would almost certainly appear in the official parliamentary records. [11]

Parliamentary Archives: the 1601 session (43 Eliz. I) deals with taxes, poverty, and trade; there is no religious decree related to nativity scenes.

Historians of the Anglican Church (Fincham & Tyacke, 2007) do not report any such measure between 1547 and 1700.

2. Iconoclasm and Religious Reforms:

It is true that the Protestant Reformation in England, especially under the influence of Anglicanism and later Puritanism, led to periods of iconoclasm — the destruction of religious images and objects considered idolatrous. This included altars, stained glass windows, and other representations seen as remnants of Catholicism. However, these actions were part of a broader ecclesiastical reform, not a specific 1601 decree against nativity scenes with capital punishment.

The attacks on images occurred mainly between 1530 and 1550 (during the reforms of Henry VIII and Edward VI) and again under Cromwell (1640‑1660). No legal record mentions a “Bethlehem Ban.” [12] [13]

3. The Puritan Ban on Christmas (Mid-17th Century):

The most explicit and systematic bans on Christmas celebrations, including nativity representations, came much later — during the Commonwealth and the Protectorate (1649–1660) under strong Puritan influence, not in 1601. The Puritans viewed Christmas as a pagan or “popish” holiday, full of excess and not rooted in Scripture. The English Parliament, controlled by Puritans, issued ordinances in 1644, 1647, and 1652 banning Christmas celebrations, closing markets, and declaring the day to be one of fasting and labor. Penalties for defying these bans included fines and other sanctions — but not the death penalty specifically for owning nativity figures. These bans were unpopular and were overturned with the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19]

Historians of the Anglican Church (Fincham & Tyacke, 2007) record no such measure between 1547 and 1700. Kenneth Fincham and Nicholas Tyacke are highly respected historians and authorities on the religious history of England during the Reformation and the Stuart period. Their works are considered foundational in the field. [20] [21]

The claim, reproduced on sites like Catholic.net and later copied by Wikipedia without verification, illustrates how a falsehood disguised as a historical fact—sensationalist and morbid but lacking any sources—can infiltrate the written tradition.

The death penalty is the most extreme form of punishment, and attributing it to a non-existent law without any proof is not just a mistake, but a serious historical distortion.

Methodological Note: In the Nativity Scene Manual, I strive to back every statement with primary sources or academic research. Even so, mistakes are possible; I encourage you to consult the cited references and let me know if you spot any inaccuracies.

The famous phrase "To err is human, to forgive divine, to correct is wise." Although often popularly attributed to Homer, the first part ("To err is human, to forgive divine") was popularized by the British poet Alexander Pope in his *An Essay on Criticism* (1711). The addition "to correct is wise" completes a crucial idea: true wisdom lies in the ability to recognize, accept, and amend our own mistakes.

The 1955 Rome Congress: a Nativity “Salon des Refusés”

We’ve traveled back in time to unpack the “unanimous” approval of Joan Amades’s definition. What emerges is not a single truth, but a complex weave of ethnographic intentions and artistic innovations that calls for reflection.

The paradox of unanimity

Joan Amades envisioned a nativity scene centered on the panoramic landscape. While valuable from a folkloric perspective, this definition excluded the single-frame diorama promoted by the Barcelona School of Nativity Art since 1912. How could such a restrictive model receive unanimous approval in Rome when, even in Barcelona—where the diorama was already practiced and appreciated—different approaches were being taken?

Deliberate framing?

No detailed minutes of the Congress have been preserved—only the final declaration. All signs suggest that unanimity was intended to establish a minimal common ground, not an exhaustive endorsement of every sensibility. Still, the resulting framework proved too rigid: it excluded dioramas and left no room for future innovations like living nativity scenes or mountaintop nativities.

A critical lesson

Not every congress consensus is infallible. Just as with Manet and the 1863 Salon des Refusés, living practice eventually corrects the jury. Our role, as lovers of nativity art, is to preserve tradition while not shying away from its contradictions.

Which of today’s “unanimous” views will need their own “Salon des Refusés” tomorrow?

Today’s “unanimous” decisions—whether in nativity art, in the arts, or in any cultural field—may become obsolete, challenged, or even surpassed in the future, just as the 1955 Congress excluded the diorama.

Which ideas, beliefs, or consensuses we hold as absolutely true today will stand the test of time?

Which ones will be seen tomorrow as errors, misguided dogmas, or even absurdities, and will need to be relegated to a “gallery of the obsolete or mistaken”?

I placed that 1955 definition in my own gallery of the obsolete a long time ago.

And you… are you still in the gallery of 1955?